Torii Kiyonaga

Japanese, 1752 - 1815

- - - - - - -

Kiyonaga was the son of an Edo bookseller and a pupil of Kiyomitsu, third in the traditional line of Torii artists. Although not a blood relative of Kiyomitsu, he assumed the duties of Torii IV following the death of his teacher, and later abandoned his own career in order to train Kiyomitsu's infant grandson into the title, Torii V.

Kiyonaga, perhaps more than any other artist in ukiyo-e, was highly praised both in his lifetime and later. He was considered by many critics in the past as "the most complete artist in all of ukiyo-e." Today, the accolades of past praise have waned and we find comments such as "dull" or "lacking in warmth" common criticisms of his style. Indeed, there was a tendency in the early days of ukiyo-e toward an extravagant praise, brought about by a certain infectious enthusiasm for his so-called "moral strength." Apparently few in those days came in contact with his erotic prints, or they would have most assuredly condemned his art as they did Utamaro. But to deny Kiyonaga's position in the crucial decade of the 1780s would be as serious an error as to claim that he was the summit and culmination of all ukiyo-e.

In design, Kiyonaga was really a genius. He was perhaps the greatest master in the allocation of space on a flat surface that the visual arts has ever produced. His sense of emphasis and balance was uncanny in its sheer perfection. He was also a pioneer in the use of color, producing stronger color harmonies than ever tried before. Moreover, his draftsmanship was poetic and evocative, yet always strong and sure. But above all, Kiyonaga introduced a new style that was to save ukiyo-e form crystallization and was to set a whole new generation of ukiyo-e artists into energetic and creative activity. Kiyonaga discarded the charming idealism of earlier artists such as Harunobu, and building on the manner already established by Koryüsai and Shigemasa, he strove for a new realism in his figures, positioning them in "real" space. Indeed, his backgrounds are no longer flat foils for figural activity, but are vast landscapes that presage the great scapes of the 19th century in ukiyo-e. It was his total vision of tall statuesque women set against fully realized backgrounds that was to form the basis of Utamaro's style. By the time of Utamaro's success in the early 1790s, however, Kiyonaga ceased to concern himself with his ukiyo-e achievements, designing but a few prints in the last two decades of his life.

- - - - - - -

KIYONAGA GLOSSARY

Asanoha: A geometrical pattern based on hexagons.

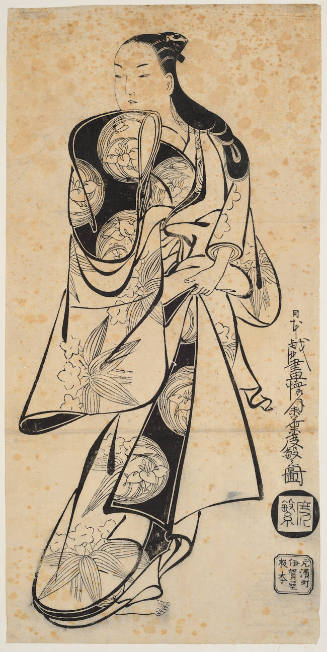

Furisode: Literally, "long sleeves." A long-sleeved kimono worn by young unmarried Japanese women. During the Tokugawa period boys also wore it.

Fusuma: A sliding door dividing a room from another, or from a closet. A "fusuma" consists of a wooden latticed frame covered with several layers of paper pasted together and finished with cloth or a plain or fancifully printed or painted paper, and with a wooden edge either plain or lacquered.

Hakama: Wide trousers with pleats worn by both sexes. Those used by ladies of the Imperial family and nobility are made of red or dark-reddish purple silk poplin, either long or short. Men's are made of plain or of striped cotton or silk, damask, or brocade, according to social rank.

Hakoya: A servant, either male or female, who escorts a geisha and carries her samisen box.

Haori: A coat worn over a kimono either in or out of doors by both sexes. In the Tokugawa period a haori for a woman was considered to be informal and in bad taste, while one for a man was used freely. Among the lower classes men wore it only on formal occasions.

Juban: An undergarment. A long one hangs to the heel and a short one above the knees.

Kamuro: A girl attendant to a yüjo, educated and trained in many accomplishments and in good manners in order that she may become a yüjo on reaching womanhood.

Kasuri: A splashed or blurred pattern in a textile.

Kataginu: Upper part of a "kami-shimo" (a formal suit made of linen, worn over a kimono by all classes of men, except noblemen in the Imperial court during the Tokugawa period). When a kami (upper part) is made of silk, it is called "kataginu."

Komusö: The popular name of the priest of Fuke-shü, a branch of the Zen sect. This branch is a peculiar one; the priest neither shaves his head nor observes commandments, but wears a priest's costume and a deep straw hat, and begs alms by playing a religious tune on a "shakuhachi." In other words, those who belong to this order are half priest and half layman. Political refugees and spies temporarily entered this sect in the Tokugawa period. It was disbanded in 1881 by a government order.

Miko: A virgin servant to a god. Among her duties is dancing in order to appease the god, based on the legend of Uzume, the goddess whose dancing pleased Amaterasu, the sun-goddess, when she hid herself in the cave out of anger against her brother, Susanoo.

Obi: A long, stiffened sash, part of the Japanese costume. Married women sometimes tied it in front. Yüjo wore the bow of an obi in front, except when going out to some place other than their own quarter. Others made a bow in the back. There are various bows tied according to age, rank, or occasion.

Shakuhachi: A wind instrument made of bamboo with four holes in front and one in back. It was invented in China and imported to Japan in the sixth century. This instrument is used for both religious and secular music.

Shigoki: An un-sewed silk sash tied around a woman's day- or night-dress.

Shinzo: A newly-married woman, particularly when addressed by inferiors; a young woman attendant to a yüjo; a new yüjo.

Shippö: A geometrical design consisting of four interlocked circles. There are many variations.

Tsuitate: A screen of one square leaf set in a frame with a stand.

Uchikake: Also called "kake" or "kaidori." A long, lined robe loosely worn over a kimono by noble ladies of yüjo.

Uchiwa: Flat fans, most of which are round. Some are irregular tetragons or hexagons, however.

Yüjo: A courtesan.

- - - - - - -

Research by: Howard A. Link.

Person TypeIndividual

Terms