Okumura Masanobu

As with most major ukiyo-e artists, biographical information on Okumura Masanobu is scant. Beyond a multitude of personal names and pseudonyms, (Inoue Kazuo, UK, Vol. II, No. 3, 1926) the main facts seem to be that he was born in the 1680s, commenced his career with a series of album illustrations in 1702, opened his own print and book publishing firm by the early 1720s and claimed credit for many of the technical innovations that changed ukiyo-e from a broad and vigorous to an increasingly subtle art form during his lifetime.

Masanobu's date of birth is deduced from the colophon of a book illustrated by him in 1703, which notes his age as eighteen. His date of death, 1764 at the age of seventy-nine, as recorded in Sekine (1899) would seem to confirm the assumption, although the source of this information is far from reliable.

A master of boundless energy, he was increasingly active from 1702 until the early 1760s. The work thus spans the entire range of technical advancements in the Primitive period. Innovations he has credited to himself include the perspective print, the pillar print, the highly-colored lacquer print, and even two-color printing. Whatever the validity of Masanobu's claims regarding these advancements, he was amply rewarded with the unequivocal praise of plagiarism, and his prints often bear advertisements for himself as the one-and-only, and admonishments to beware of unauthorized forgeries.

Masanobu was also a fluent writer and illustrator. His intelligence, seriousness and unconventional humor, set him apart from his contemporaries and his woodblock prints rank among the finest in the entire "ukiyo-e" school.

The Michener Collection is especially rich in work by Masanobu including several early album pages of exceptional wit and vigor and a large number of harmoniously designed single sheet prints from the 1720s to the 1750s, among them some impressive studies of actors in large kakemono format.

- - - - - - -

Masanobu's birth date is still a matter of varying opinion. In both Yoshinara's "Meiyo Orai" and Shisei's "Meihin Ishin Roku," the statement is made that Masanobu died at the age of 79 in either 1768 or 1764. Sekine writing in 1894 suggests 1768, but in his research of 1899, he subscribes to the date 1764 and the age 79. Depending on which death date is correct, he was born in either 1691 or 1685. In support of the 1691 theory, there survives a six-paneled screen of a theater performance given at the Nakamura-za. The name of the play, Fububiki Nagoya, clearly visible on the screen can be confirmed in the "Hana no Edo Kabuki Nendaiki," a fairly reliable Kabuki history compiled by Emba Danjürö. More importantly the date Kyöhö ju-roku nen (1731) is inscribed on the screen along with Masanobu's age of 41 years. Scholars now believe that the inscription is either a spurious addition or a mistake, for more convincing evidence has come to light proving the 1764 date to be more likely.

The earliest surviving book signed Masanobu appears in 1701 and although imitative of Torii, would still seem to be too advanced for a ten year old child. Moreover, in 1703, Masanobu published another book, titled "Kyotaro," the colophon of which includes the statement that Masanobu was eighteen years at the time of publication. In addition Inoue reports the existence of a painting of a "bijin" with the inscription "Konen nan junisai ga." The design in question, on stylistic grounds comes from a time toward the close of Masanobu's life and suggests that the 1685 date to be the more likely. We therefore subscribe to the opinion that Okumura Masanobu was born in 1685 and that he died in 1764 at the age of 79. Without burial records or tombstone materials, this is as close as we can come to dating our artist’s life. With biographical materials almost totally lacking, it is in the art itself that we find our only evidence for reconstructing the life of our artist.

A complete catalogue raisone of all the surviving works of Masanobu has yet to be accomplished. We are largely dependent on the work of Inoue Kazuo (noted above) for his compilation of the surviving book art and Shibui Kiyoshi for his work in album sheets for some idea of Okumura's stylistic development in the early years. In the area of single -sheets we have seen two or three hundred out of a total corpus which must be close to a thousand. From all this material we can reconstruct with a fair degree of accuracy his artistic development and technical achievements. His working period begins in 1701, the time his first signed book, and ends around 1756 when his single-sheets seem to stop. His earliest work is done in the Torii style, as was most art of the day, but beginning in the 1720s he combines elements from the Torii as well as the art style of Nishikawa Sukenobu to produce a softer more elegant style that suited his own literary temperament better. Toward the closing years of his activity beginning after 1740, his work takes on unevenness and some prints signed by him or attributed to him appear to be from the hands of a hack artist or artists working in his studio. When the chaff has been separated from the large output, it is clear that the master maintained an extremely high standard throughout his entire artistic career. A chronological review of the signed and dated work of Masanobu follows.

- - - - - - -

Masanobu's first signed and dated work appeared in 1701. The e-hon titled "Shögi Gacho," which also can be read "Keisei e-hon." It seems to be a copy of a book published a few months earlier in 1700 which is signed Torii Kiyonobu. The Masanobu book is dated in colophon to the 6th month of Genroku 14 (1701) and is signed "Wa Gakö Okamura Genpachi Masanobu Zu". The publisher is Kurihara Chöemon of Ha segawachö. This book followed the style of the Torii school as did all his other books up until 1715. In 1703 there appeared two more books totally imitative. Indeed between 1704 and 1715 there appeared fifteen more "ukiyo-zöshi" and four "rokudabon" all done in the Torii style.

Inoue Kazuo lists a total of fourteen "sumizuri-e" albums by Masanobu in various states of completeness, and although none of these are dated, style considerations and comparisons with the dated book art suggests that they were also the product of the first fourteen years of Masanobu's artistic career. Shibui Kiyoshi's dating of album sheets confirms the basic dating suggested here.

As for Masanobu's single-sheet art, we are limited to Kabuki subjects for firmly dated materials, and in this genre Masanobu betrays little of the inventiveness that occurs in his other subjects. Sometimes his Kabuki subjects follow the style of Kiyomasu II and very occasionally the style of Kiyonobu II. The scholarly community has been able to date single-sheets to as early as 1723 and as late as 1756 (cat. 32). The Academy collection includes prints firmly dated to 1744 as well as 1749 (cat. 27). In other collections, there are prints dateable to 1725, 1727, 1731, 1733, and 1736. Thus we have a fairly uninterrupted picture of our artist’s work in Kabuki throughout his long career.

Masanobu's "e-hons" continue to appear sporadically, and of the nine that are known to survive, four include the dates of 1723, 1734, 1736, and 1752. Often the influence of Sukenobu can be felt in this book art.

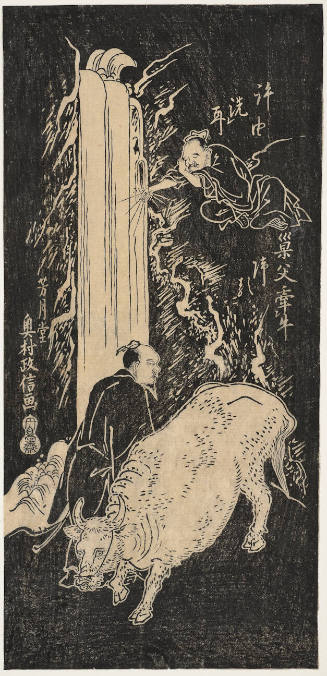

After 1740, several technical innovations occur and with each innovation a slightly different style is adopted. Among the innovations are "ishizuri-e" (cat. 30), "uki-e" (cat. 29), "hashira-e," and in 1747 "benizuri-e."

It is said that Masanobu pioneered many of these technical novelties and there seems little reason to doubt some of the claims. In addition to his technical achievements (which might be as much the work of his son Genroku), he most certainly pioneered the "doko-e" or comic print. He had a keen wit and sharp mind which is clearly visible in his "hanjimono" (puzzle) prints and in the many delightful albums full of travesty and literary puns. In the final analysis, we would have to agree with C.H. Mitchell of the Japan Ukiyo-e Society who has hailed his prints as "among the most magnificent and most important in all of ukiyo-e".

- - - - - - -

DETAILED DICUSSION:

Despite the obvious importance of Okumura Masanobu to the early history of ukiyo-e, a thorough study of this artist's life and work has yet to be accomplished. The earliest research of merit was accomplished by Miyatake Gaikotsu in Meiji 43 (1909) entitled "Okumura Masanobu gafu." The work contains specimens of his art, brief investigations about his life and his disciples, and two hitherto unknown but significant facts.

Our artist's formal name was Shinmyö, while his personal name was Genpachi or Genpachirö. The formal name Shinmyö had previously listed in all compilations as Kanmyö, but the reading had been corrected by Miyatake in the above mentioned monograph. Moreover, our Meiji researcher suggested that Masanobu received training in "haiku" with the master Shotetsudö Fukaku Sen'o. This suggestion is based on the Masanobu signature, Hogetsudö Bunkaku Baiö which appeared on certain prints by our artist. Finally, Miyatake noted that none of his work in the Höei and Shöteku periods emanated from his own print shop, suggesting that he did not enter the publishing business until a later date.

Inoue Kazuo, writing in 1926, (see "Okumura Masanobu" Ukiyo-e no Kenkyü, II, No. 3, Tokyo, 1926) added some important biographical refinements, and helped to round out the list of known surviving illustrated books. One of Inoue's theories dealing with the identity of the artist signing himself Okumura Genroku, is now generally accepted by the scholarly community. Inoue suggested that all prints signed Okumura Genroku, are not by the first Okumura Gempachi (e.g. Masanobu) but rather by his son or disciple. The basis for his theory is the total absence of the name Genroku in prints using the Masanobu appellation. That is, whenever the name Masanobu occurs, and it is always in connection with the name Gempachi, never with Genroku. He dates all the known Genroku prints to the 1720s and 1730s, but notes that although Masanobu's prints from 1724 onward were produced by the Okumura-ya, that none of Genroku's prints come from this publisher. Such an anomaly has no ready answer, but we should note that prints by Masanobu's other disciple, Toshinobu do not emanate from the Okumura workshop until after 1740.

With the discovery of more prints signed Genroku, it appears that he worked in the designing of ukiyo-e up until around 1740, at which time he quit the art field and entered the publishing end of the business. We may note that no prints signed Genroku can be dated after 1741, and that prints by Okumura Masanobu bearing the Tochösai art name will inevitably include the Genroku name in the publisher’s information. We have mentioned in our summary, that certain critics subscribe to the theory that there were two artists utilizing the Masanobu appellation, one the first master, and the other a drudge. Perhaps this hack artist may someday be identified with Genroku who may have begun to publish under the name of his illustrious father in the 1740s. Indeed, the decline which some critics note in certain works signed Masanobu is in unbelievably sharp contrast with the superbly satisfying prints by Masanobu of the same late period. Such unevenness usually suggests the presence of two artists utilizing the same signature.

- - - - - - -

Lively Wit and Invention

Summary:

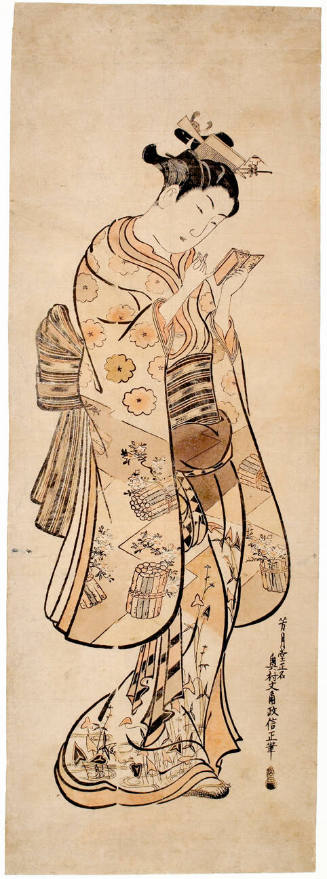

Masanobu's work spans almost the total range of the Primitive period starting with the large-scale "sumizuri-e" in 1701 and ending with the "benizuri-e" just before the advent of full-color printing in 1765. A vastly underrated artist who has yet to be thoroughly studied, we believe that Masanobu was a master of great ability and virtuosity. His earliest work is done in the Torii style (cat. 22) but he was quick to develop a wit and verve that was to underline his best designs in the early years. Many of his album sheets reveal a fondness for parody (cat. 24) while with the growing interest in a greater realism (which can be paralleled in the Kabuki theatre as well) he increasingly turns his interest to the successful designing of colored prints, either his fine "urushi-e" or his later "benizuri-e." In addition to his successes as an artist, he was an established bookseller and publisher, and his flamboyancy as one of the Edo "chönin" (merchant class) is clearly visible in his own bold appraisals of his work. Curiously, his art is rather uneven in quality, and it has seriously been suggested that some prints signed Okumura Masanobu are actually the work of a hack artist working in his studio. The majority of designs thought to be by the great master fully support the opinion that "his art is among the most magnificent and most important in all of ukiyo-e". His inventive genius and love of experimentation are clearly shown in the examples selected here which include early picture book art, dazzling sumizuri-e album sheets, exquisite large-scale "urushi-e" designs, satisfying "benizuri-e," novel "uki-e" (perspective pictures) and even "ishizuri-e" (white on black printing). Many of these techniques may have been pioneered by our versatile artist.

24. Nakada Katsunosuke, "Ehon no Kenkyu" lists the following early books:

Yoro no Taki 1704 2 vol.

Yusho Otogi zoshi 1706

Wake no Riko 1706 5 vol. Ukiyozoshi

Danshoku Hiyoku no Tori 1707 6 vol. Ukiyozoshi

Hoyoku Renrimaru 1707 Ukiyozoshi

Wakakusa Genji Monogatari 6 vol. Ukiyozoshi

Furyu Kuretake Otoko 1708 5 vol. Ukiyozoshi

Hinazuru Genji Monogatari 1708 6 vol. Ukiyozoshi

Furyu Kadode Kazogura 1708 5 vol. Ukiyozoshi

Kanto Nagori no Tamoto 1708 5 vol. Ukiyozoshi

Motozodaishi Omikujisho 1708 5 vol. Ukiyozoshi

To Genso 1708 1 vol. Rokudanbon

Kohaku Genji Monogatari 1709 6 vol. Ukiyozoshi

Kanjun Iro Habutae 1709 5 vol. Ukiyozoshi

Furyu Kagamigaike 1709 6 vol. Ukiyozoshi

Koshoku Yugao Toshioigusa 1709 5 vol. Ukiyozoshi

Wakakusa Genji Monogatari 1710 2 vol. Ukiyozoshi

Hachiman Taro 1710 1 vol. Rokudanbon

Sanko Gunki 1710 1 vol. Rokudanbon

Sansho Dayuu 1710 1 vol. Rokudanbon

After 1710, he did not work much on book illustration except one work called "Bukeshoku Gensho", 2 volumes in 1716. His early Ehons are published between 1700 to 1715.

Research by: Howard A. Link.