Tōshūsai Sharaku

Japanese, active c. 1794 - 1795

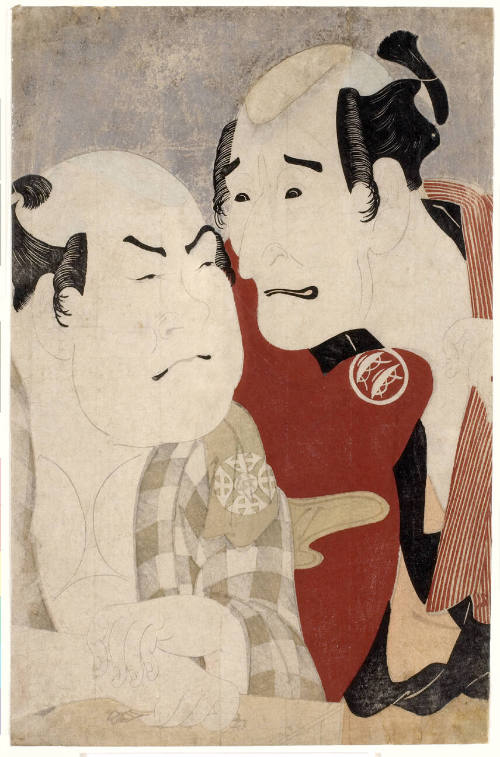

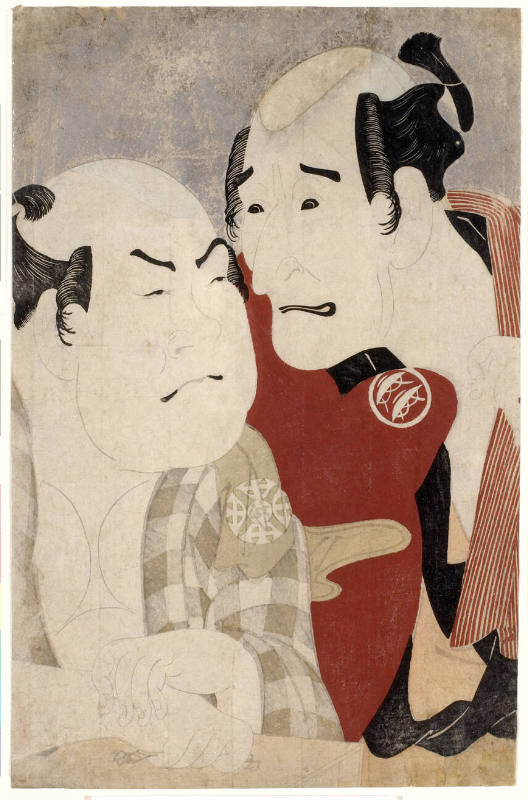

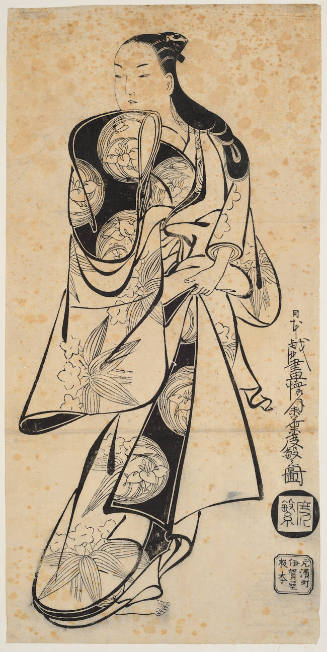

Sharaku is well represented in the Academy collection. Michener gathered nine bust portraits in ö ban size, all in fine condition, including one dynamic group composition, and one standing actor in hosoban size. All of these prints can be dated to plays performed in the second half of 1794.

- - - - - - -

In the field of art history, the student is often beset by the difficulties in determining the most advantageous approach to the study of a given artist and his works. Should the particular artist be considered in relation to his contemporaries, vis à vis their schools and movements? Or should his works be treated in the light of their stylistic peculiarities and/or technical advances? Or should his subject matter be viewed as a social commentary of his times? For the purposes of a study of Töshüsai Sharaku (worked 1794-1795), the above questions may be ruled out, however fascinating. The ultimate aspect of this artist -- his identity -- remains one of the great enigmas of Japanese art. Indeed, Sharaku is but little more than one of the ghosts of art history referred to by historians as "anonymous artist".

Although his name appears on well over 160 masterpieces, all apparently accomplished in 10 months, we know almost nothing about him. This fact is all the more surprising when we consider that Japan of this time was not without documentation on Sharaku's contemporaries. Scholarship on Sharaku is abundant. In Germany there is the pioneer work of Julius Kurth and Fritz Rumpf; in England there is the unpublished research of Binyon and Sexton (notes in possession of Jack Hillier); in America there is the monumental study of Henderson and Ledoux; and in Japan there is the work of a host of other critics who have made abortive investigations into Sharaku's hypothetical biography, as well as the distinguished research of Nakada, Yoshida, Inoue, and recently, Suzuki Juzö. The results of all this investigation, while bringing us closer to an understanding of Sharaku's working period, add nothing to our knowledge of his identity.

The recorded evidence: Suzuki Juzö offers the most recent study of the artist, Töshüsai Sharaku, adding some interesting refinements to the otherwise authoritative work of Teruji Yoshida. It is from the work of these two scholars that the following summary is taken: The earliest account that makes reference to Sharaku is dated 1831, but is based on materials that date back as early as the late 1790s. The record is called the "Ukiyo-e Ruikö". The earliest reference reads: "Sharaku has tried to be so true to life in his portraits of actors that he had gone to unpleasant extremes, had proved unpopular as a result, and had a productive life of a mere year or two" (Suzuki/Bester translation). This statement was written in the late 1790s, according to Suzuki. By the time the work had been transcribed around 1805 Kantö Eiban had added: "Nevertheless, he is worthy of praise for the stylishness of his line" and shortly after that Sambe Shikitei added the statement: "Sharaku, art name Töshüsai, dwelt in Hatchöbori, Edo; was popular for only half a year" (Yoshida/Mitchell translation). Thus, all the truly contemporary information on Sharaku that appears in the 1831 version confines itself to the vaguest of outlines.

The most important reference and one to which much thanks for the discovery must go to Suzuki Juzö, appears in the "Zöhö Ukiyo-e Ruikö", dated in colophon to 1844. It reads: "A figure (jimbutsu) of the Temmei era (1781-1788) and Kansei era (1789-1800) dwelt in Hatchöbori, Edo. A Nö actor in the troupe of the Lord of Awa ... frequently used mica dust for his backgrounds." The note exists in the author's original hand. But who was the author? Aside from his name, Gesshin, virtually nothing is known. (We have abundant information on the life of the other writers so far mentioned.) Moreover, what was Gesshin's source? Can the scholarly community completely accept a statement with no apparent antecedents written some 20 years before Meiji and some 50 years after the fact? It also notes that Sharaku was a figure of the Temmei era (1781-1788), and yet there is no surviving art that can be successfully dated to this time. Thus one can only conclude that the evidence is too weak to be decisive. The Nö actor theory is not a new one. The same passage occurs in the published "Ukiyo-e Ruikö" of the 1880s, but until Suzuki's 1840 discovery, the passage was generally thought to date much too late for serious consideration.

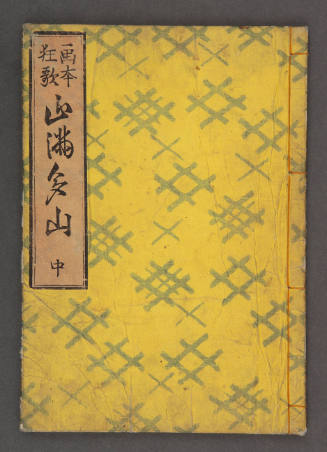

Fact or Fiction?: If one investigates thoroughly the fifty years of painstaking research to confirm the existence of Gesshin's Nö actor, one would uncover countless discoveries followed by theory, followed by refutation, with very little that is certain. The scholarly community is not even certain of the actor's name, although most seem to list Saitö Juröbei as the more likely. Until the discovery of some basic contemporary source directly linking the two, the Nö identification must be approached with caution. The late Kondo Ichitarö, former Curator of the Tokyo National Museum, sums up the matter with these comments: "In spite of all these efforts, since the name Saitö Juröbei does not appear in the various records or tombstones identified as his, one cannot avoid the suspicion that they do not actually refer to Saitö Juröbei, much less Sharaku. In other words, all this research seems but a futile attempt to justify data of unknown origin. I am not alone in not being able to rid myself of the uneasy feeling that all the Nö actor endeavor may be nothing more than pure fiction." But without any new or better information to put in its place, most historians have been content to accept the theory with a certain futility that nothing new will ever be discovered. New evidence, however, continues to appear and even new prints. For example, just recently two new Sharaku designs were uncovered in a museum collection in Brussels by Roger Keyes and Jack Hillier. There are probably still many more lost in private and museum collections, particularly in Europe. Evidence including a map and a novelette illustration (recently discovered by Suzuki Juzö), though adding only a minor side light to our knowledge, suggests that there may still be more evidence buried away in the archives of some library.

In the meantime, the world must content itself with the proposal that an untrained amateur from a social, cultural, and artistic background completely alien to the Edo-Kabuki-ukiyo-e traditions burst upon the Edo scene, produced a body of 160 masterpieces in a period of around 10 months and then vanished without a trace. The art itself offers our safest evidence, but even here there are many perplexing problems.

The Surviving Art of Töshüsai Sharaku: Kabuki dating must always be approached with a degree of caution. When a print is uncovered that seems to fit a particular scene from a known play, scholars have been quick to identify the print to the particular play. As a result, mistakes of up to 20 years have occurred. The history of the dating of Sharaku prints is a classic example of the problems encountered in Kabuki dating.

The pioneer work of Dr. Julius Kurth, the first critic to publish Sharaku's surviving art (a very provincial selection, however) speculated a period of nine full years of activity from 1787 to 1796, at which time he used the name Kabukido Enkyo. Inoue Kazuo believed that he worked for a period of 17 months, beginning in the first month of 1794 and concluding at the end of the fifth month of 1795. Inoue came close to current opinion, as did Fritz Rumpf, although the precise roles have been corrected in many cases. Kanchiro Hatano, who was willing to accept many designs of a more controversial nature, attempted to prove a 19-year working period from 1786 to 1804. All this work has been overshadowed in recent years by the 10-month theory (e.g. the fifth month of 1794 to the 2nd month of 1795), first introduced by the American critics, Henderson and Ledoux in 1939 and since corroborated in the work of Yoshida Teruji and Suzuki Juzö. Both Yoshida and Suzuki uncovered some important Kabuki materials (playbills, etc.) that made it possible to correct some of the identifications offered by Henderson and Ledoux, but in no case were the basic outlines of the identification or the 10-month period of activity challenged. Here we have proof of what Western scholarship can do in this difficult area given the opportunity. The majority of Sharaku's prints are pictures of actors (only a few sumö and warrior pictures were attempted) and they may be delivered into four distinct periods. Within ten months we have the evolution of an artist's work that normally would be observed in a decade with an ordinary artist. Moreover, his best work appears first, and his more ordinary work appears last.

Period I: Twenty-eight prints, inspired by plays performed at the three Kabuki theaters during the fifth month of the 1794 season. All are half-length portraits in large size with mica dust backgrounds. Here are his unrivaled portraits, revealing a near-caricature approach that borders on psychological portraiture (which comes closer to Western taste than to the traditional Japanese portrait idiom). Aside from Utamaro's intuitive perception of female vanity, and the occasional "psychological" portraits seen in the work of Shun'ei and before him, Ryukösai, Sharaku's approach was entirely new to ukiyo-e. The Michener Collection contains four superb prints from this most important and rare series.

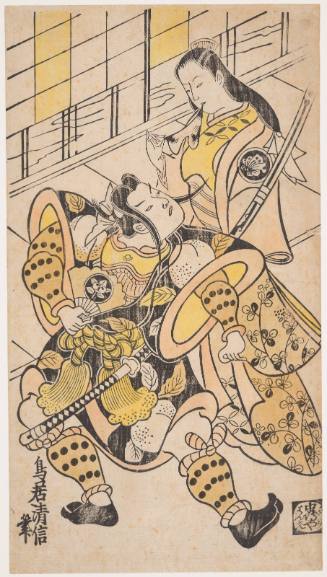

Period II: In the 7th and 8th months of 1794 there survive a total of thirty-eight designs inspired by plays given at this time. Eight of the designs are in large format and thirty are done in the small narrow format preferred by Katsukawa Shunshö. The large format sheets reveal Sharaku's dynamic ability at group compositions and there is no lessening in power, but in his narrow panels of single standing figures he seems content to follow the time-honored formula established for the Katsukawa school with only a superficial adherence to the initial biting quality of his portrait studies.

Period III and IV: Sharaku briefly returned to the bust portrait format in plays celebrating the Kaomise (face-showing) performances at the Edo theaters presented in the 11th month of 1794. These prints lack the fineness of his earlier half-length portraits and seem closer to the general style of Shun'ei, a pupil of Katsukawa Shunshö. His dozens of narrow panel prints of standing figures continue the tradition established by Shunshö, adding very little in the way of vitality or originality. In all cases, the signature reads merely "Sharaku 'ga'" and the usual mica background is omitted.

Interpretation and Speculation: As Suzuki Juzö notes: "The usual course followed by Ukiyo-e artists took them from a comprehensive treatment of the whole subject together with its background, to a full-length treatment of isolated figures without a background and thence to the half-length figure; from the small print to the large print; and from technical simplicity to the technical complexity. Sharaku travelled in precisely the opposite direction." Suzuki speculates no further, but the present writer believes that a clue exists in all this that may someday prove useful to discovering the artist's true identity. The evidence suggests a long period of prior development in which the full-figure was first considered. Moreover, ten months cannot be compared with a decade of artistic development in any event, yet historians insist on thinking in these terms in the case of Sharaku. It seems clear, therefore, that we are dealing with an already proficient artist experimenting with facets of an already developed art style.

There have been several attempts to identify Sharaku with other artists of the time, and although often wild and unfounded theories have resulted, the entire name-change thesis remains an intriguing possibility. The study of Toyokuni's famous portrait series, "Views of Actors on Stage", proves that while there were important cross-influences between these two artists, we are clearly dealing with two distinct artistic personalities. In 1910, Julius Kurth, who first brought Sharaku to world attention, proposed that a follower of Sharaku, Kabukidö Enkyo (who apparently worked for only about six months in 1796), was in reality Sharaku; but a close examination of Enkyo's art does not support such a claim and Kurth's supposed "recorded evidence" is nothing more than some Meiji period "opinion" expressed as fact. A color psychologist, Taguchi Ryüsaborö, has even suggested the master, Okyo, but the entire theory proved too weak for serious consideration. Most recently, a prominent Japanese critic suggested Hokusai, and while there seems to be some minor support, the theory has been coolly received by the scholarly community.

Despite these apparently abortive attempts, we believe that the name-change theory still offers the best hope for a final solution. Among Sharaku's surviving works that have generally been accepted as authentic are several designs done in an entirely conventional style. Two works, the God Ebisu and a fan painting showing a chubby-faced character (Okame, a Shintö deity throwing beans) follow the traditional formula for such subjects. Several portraits of Sumö wrestlers survive that show little of the Sharaku "bite" of his initial big-head actor portraits. All these designs are similar to the art style of the Katsukawa school which dominated the theatrical world in the early 1790s. One Sharaku design showing the warriors, Soga no Gorö and Gosho no Goromaru, comes surprisingly close to the style of Hokusai (alias Katsukawa Shunrö), giving small support to those who insist on equating these two artists. And after the end of the Pacific War in 1946, the Sharaku scholar, Yoshida Teruji, discovered a Sharaku print entitled "Yakusha-onocha-e" (actually an un-cut series of Kabuki playcards for children), that can be firmly dated to 1799. If this print can someday be fully accepted, the working period for the artist calling himself Sharaku will need to be reconsidered.

In seeking the sources of Sharaku's unique style during those first tumultuous months in the spring of 1794, fruitful results are coming to light. For example, the portraits of Yamashita Kinsaku by Sharaku resemble those found in the picture books, "Yakusha Monoiwai" and "Ehaon Niwatazumi", by the Osaka artist, Tyukösai Jökei, working in the 1780s; a direct influence seems highly possible. The biting quality of these early actor portraits matches closely those of Sharaku done some 10 years later. And Ryukösai's possible association and even friendship with members of the Katsukawa school, particularly Shunrö (alias Hokusai) provides still another clue.

Future research, once disentangled from the Nö myth, will hopefully produce a solution -- one so plausible, even obvious, that we may eventually wonder at our own blindness. For the present, the author is willing to predict that many of the above clues will prove more important to this solution and that the final answer will be based on a simple name change that resulted in the emergence and sudden disappearance of the enigma known as Töshüsai Sharaku.

Research by: Howard A. Link.

Person TypeIndividual

Terms