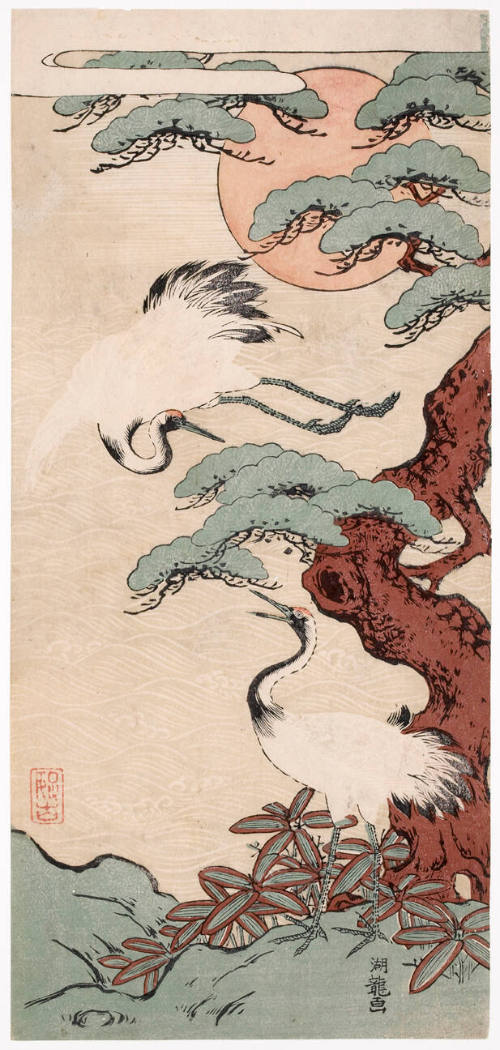

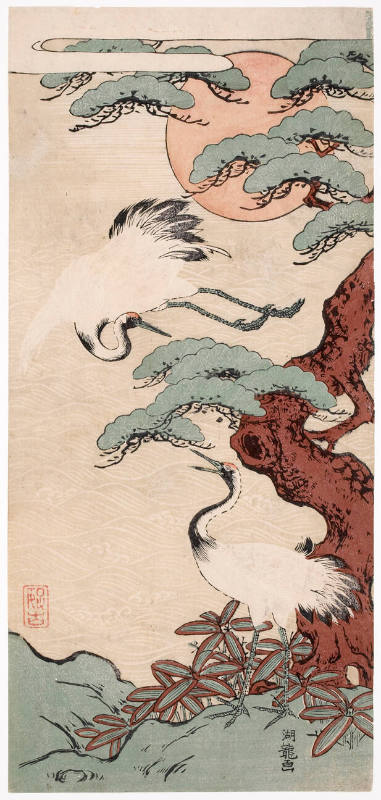

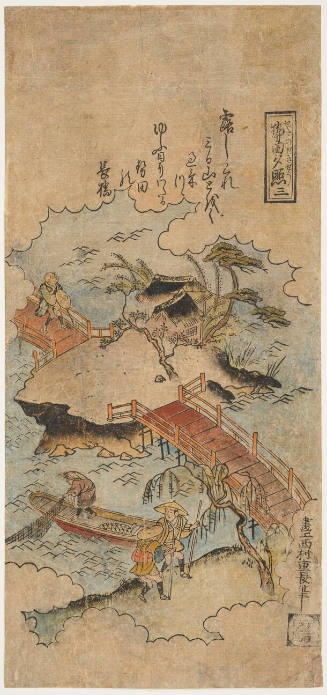

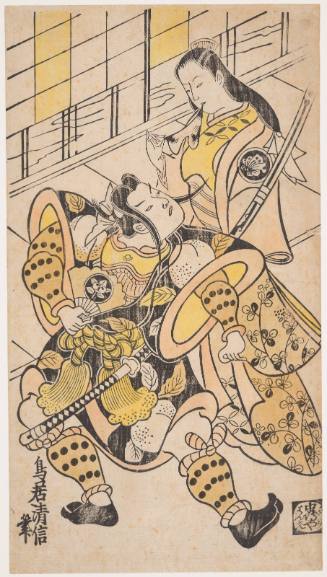

Isoda Koryūsai

Japanese, 1735–1790

Koryüsai’s later prints feature a taller, more adult and massive figure. They wear the töröbin (lantern) coiffeurs that were becoming popular in the gay quarters by the mid-to-late 1770s. Whether he invented this new fashion plate or merely followed the style of Kitao Shigemasa, who also adopted the more massive figure with elaborate coiffeur in his work, has yet to be determined. If Koryüsai is responsible for its introduction, his position in the history and evolution of the beautiful woman portrait is much more important than previously thought. It is this more massive style of figure that paved the way for the art of Kiyonaga, and ultimately Utamaro.

In the 1780s, Koryüsai apparently abandoned the production of prints in favor of nikuhitsu paintings, according to Richard Lane. His other names include, in addition to those already mentioned, Koryü, Masakatsu, and Shöbei. He designed at least 30 print series between 1767 and 1778, and a number of important illustrated books from 1777 to 1784. His art has been underrated by critics.

- - - - - - -

Isoda Koryüsai (worked 1760-1784) is considered by early sources to be a pupil of Shigenaga, but the evidence is very weak and there is a tendency among scholars to regard him as a pupil of Harunobu. Dr. Lane escapes the question quite nicely by regarding him as a friend of Harunobu, but such a relationship would hardly account for his use of the art name Haruhiro, a name based on the first character 'Haru' of Harunobu. Many of Koryüsai's earliest designs are in the Harunobu manner, and there has been confusion between the unsigned works of these two artists. Generally, however, the exceptional critic will recognize subtle differences in the drawing, and Koryüsai's publisher always selected a darker and bolder color-scheme for his work. (Whether this was the artist's influence is a difficult question to resolve.) His finest work is in bird and flower pictures and the long, narrow pillar print. Indeed, the latter even out-do those of Harunobu in the endless variety of composition and are regarded the best in all of ukiyo-e. His later prints depict figures in öban size, which is considerably bigger than the small rectangular squares of Haruobu. His figures of courtesans, while admittedly repetitious, are more massive, and feature elaborate coiffeurs -- characteristics that presage the style of Kiyonaga in this genre. Critics tend to regard his art as second-rate. He was overshadowed by Harunobu at the beginning of his career and by Kiyonaga at the end of his career. We would suggest that Koryüsai's position in the history of ukiyo-e was an important one. He carried forward the style of Harunobu to another generation of artists, and set in motion the more stately processional style of massively robed courtesans that was to serve as the subject for countless compositions by Kiyonaga and Utamaro.

Research by: Howard A. Link.

Person TypeIndividual

Terms