Torii Kiyonobu I

Japanese, 1664 - 1729

Kiyonobu I is traditionally regarded as the founder of the school, but research in recent years has shown that at least two artists using the Torii name preceded him. Torii Kiyomoto, Kiyonobu’s father, is designated in the "Torii ga Keifu Kö" (a family record written down sometime after 1785) as an Osaka actor-artist who moved to Edo with his family in 1687. Torii Kiyotaka, although not listed in the Torii family record, is mentioned in contemporary literature ("Füryü Kagami ga Ike," 1709) as being a teacher of Shöbei (personal name of Kiyonobu I) and the veteran artist of the Torii school. Signed art by these early masters is no longer known to be extant, although a few unsigned illustrated books and a remarkable group of over twenty large actor portraits (NHBZ, vol. 2, fig. 134) in the Torii style that may be attributable to them survive from a time prior to Kiyonobu’s first great works of 1700.

Torii Kiyonobu I was probably the second son of Torii Kiyomoto and, according to the family records, including tombstone documentation, was born in 1664. Because of his great popularity he became the titular head of the Torii school, which may account for the general opinion that he was the founder of the school. He died in 1729, receiving a nine-character posthumous name, the highest status obtainable for an Edo commoner in the Nichiren Buddhist sect.

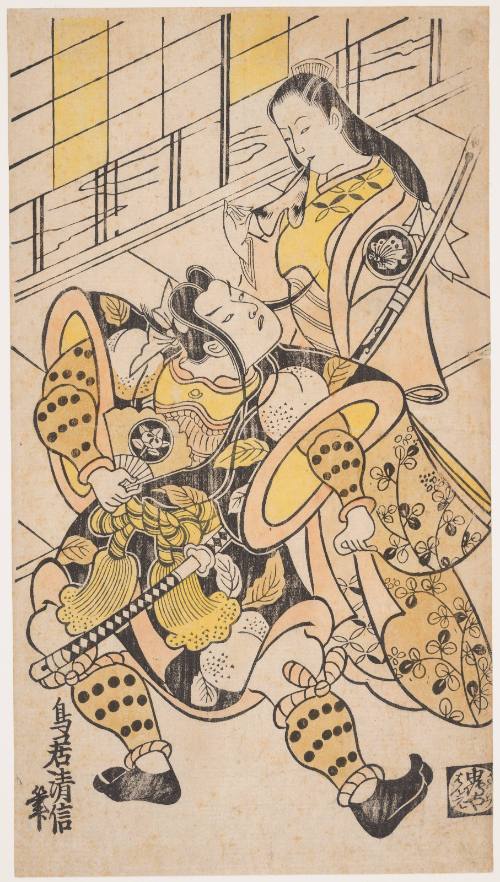

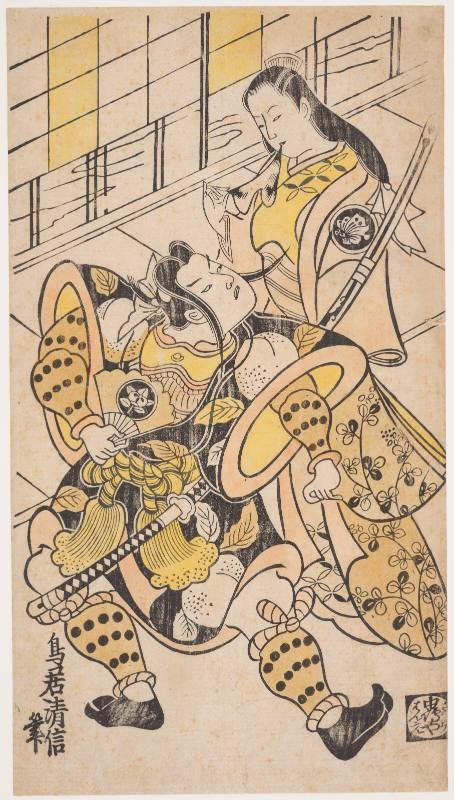

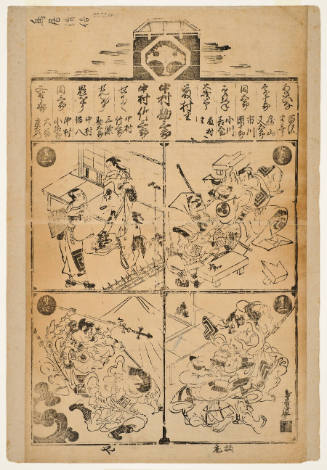

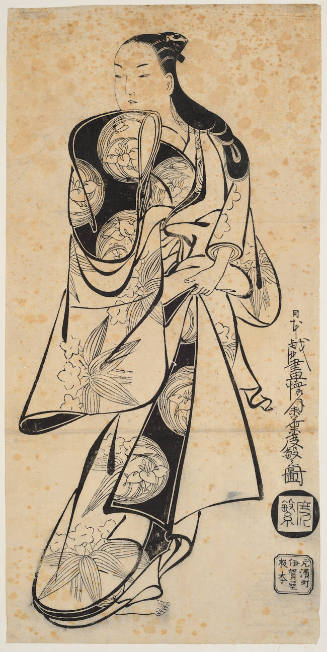

Young Shöbei emerged from the ranks of the students in 1700 to become an artist of merit and signed his new art name, Kiyonobu, for the first time in two illustrated albums -- "Fürü Yomo Byöbu" and "Keisei Ehon." The former is designed in one of the early Torii styles used for "kabuki" actors, full of drama yet contained and purely decorative. In the latter are the typical renderings of the solitary woman with emphasis on the design of the "kimono." The style of both works can be traced back to unsigned illustrated "kabuki" books of 1697 designed by an undetermined master or masters. Kiyonobu's name also appears at this time on "kabuki" playbills and erotic albums, as well as on a few single-sheets documenting "kabuki" plays of the day. The Michener Collection is represented by one erotic album sheet from this early period (Cat. No. 1).

Torii art from 1705 to the early 1720s affords a variety of interpretations. The styles of Kiyonobu I and his contemporary Kiyomasu I are very similar, and some critics, for lack of information on Kiyomasu, have acquiesced in the unsupportable hypothesis that they were one and the same person.

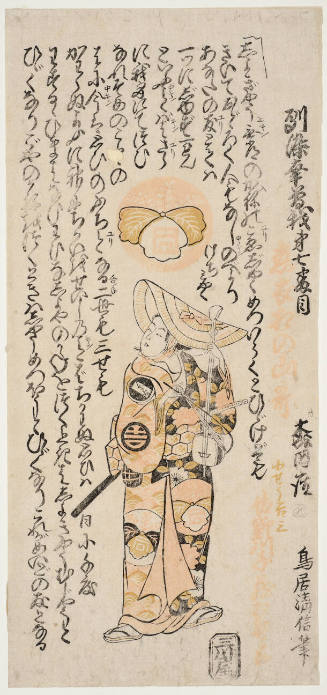

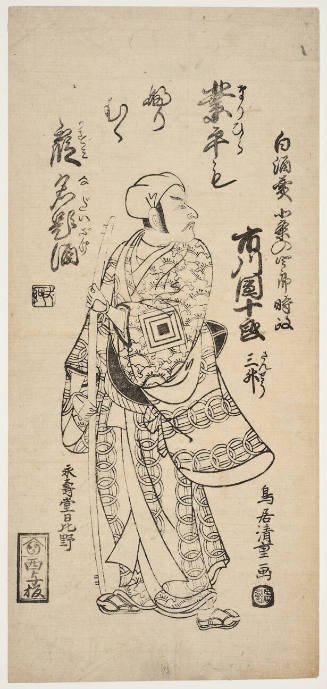

The Honolulu Academy of Art's documentation on Kiyonobu from the work of his mature years is revealed in a few choice single-sheet prints recording "kabuki" performances between 1715 and the early 1720s. These prints include portraits of such leading "kabuki" actors of the day as Ichikawa Kuzö, Sanjö Kantarö, Ichimura Takenojö, Fujimura Handayu, Ichikawa Danjurö II, and Sanogawa Mangiku -- all done in the rather static style that typifies Kiyonobu's later years (Cat. Nos. 2-7).

- - - - - - -

DETAILED DISCUSSION:

Foremost among the ukiyo-e artists of the Primitive period are the first masters to bear the names of Torii Kiyonobu and Torii Kiyomasu. Together, these artists established a standard in the representation of Kabuki subject matter that was to influence ukiyo-e art to the end of the nineteenth century. Tradition states that Torii Kiyonobu was the founder of the Torii school, and originated this style of art, and that Torii Kiyomasu, his son, came second. The foundation of this tradition however, is shaky and contradictory, and most scholars today leave open the problem of blood relationships and the touchy question of "founder". The study of these artists is further complicated by the fact that artists of the succeeding Torii generations used the signatures Torii Kiyonobu and Torii Kiyomasu without distinguishing the precedence of these masters, and adopted the same style of drawing and subject matter.

The Genealogical Reconstruction:

A brief review of the many conflicting theories regarding the identity of early Torii artists is here evaluated.

Theory I.

Based on an intensive genealogical study of the Torii family, Inoue Kazue concluded that there were two artists who used the name Kiyomasu and two artists who used the name Kiyonobu. According to Inoue's findings, both Kiyomasu I and II, and Kiyonobu II were sons of Torii Shobei, or as he was also known, Kiyonobu I.(10) Inoue's reconstruction of the artistic genealogy and his identification of the Torii family is based on the "Torii ga Keifu Kö" (Torii family record), one edition of the "Ukiyo-e Ruiko," a tombstone inscription, his inability to find prints signed Kiyomasu between 1716 and 1724, and some rather artificial deductions.

Not one single sheet in the Torii style signed Kiyonobu can be safely dated to a time before 1700. This date appears to be the year that young Shöbei emerged from the ranks of a student to become an artist of some merit. Shöbei's use of the Kiyonobu signature for the first time in 1700 suggests that his rank as an artist had been elevated and this is supported by the fact that the name appears for the first time on playbills of the Kabuki theater. Moreover, he appears to have produced "Kaomise banzuke," beginning in 1700. Shunga albums by Kiyonobu efforts begin to appear at this same time, too, according to the studies of Shibui Kiyoshi. There are several single-sheet prints of actors which begin to appear also. In 1705, Kiyonobu produced his "Füryü Budö Iro Bakkei," an "ukiyo-zöshi" done in the fully developed Torii style that first appeared several years earlier in the unsigned "ei ri-kyögen-bon" of 1697-98. (See study materials, No. 9)

Art from 1705 to the early 1720s affords a variety of interpretations. Critics find particularly in the "bijin-ga" and aragoto-style warrior pictures, which cannot be accurately dated, justification for almost any theory. (See study materials No. 10 and No. 11) While Fritz argues the idea that any art signed Kiyonobu or Kiyomasu is by one man only, pointing to admitted similarities of poses and general style, others prefer to think that they were the product of two artists, finding to their satisfaction two distinct artistic personalities. It is our opinion that Kiyonobu's art is a shade more powerful than that of Kiyomasu, perhaps because it is always a trifle awkward. The faces of Kiyonobu's figures are never as handsome as those of Kiyomasu, and there is an overall lack of refinement in his drawing. Kiyomasu's compositions are always well balanced, no matter how intricate, with a tendency to fill the entire page with drawing. His faces, particularly those of his "bijin-ga," are always the more appealing, whereas some of Kiyonobu's seem similar to the rather unrefined Kaigetsudö models.

Nevertheless, the styles of the two masters are very similar, and to the uninitiated, no doubt, their individual characteristics will be difficult to see until experience reveals that which has been seen but has gone unremarked. His art tends to become more refined and elegant toward the latter part of the 1710s, perhaps accounting for the occasional misattribution of his art to Kiyomasu. At least three extant works bear the Kiyomasu seal with the Kiyonobu signature. To confound matters still further, he died in 1729, receiving a nine-character posthumous name, which was the highest status obtainable for and Edo commoner in the Nichiren Buddhist sect. His date of birth, 1664, though listed in the "Torii ga Keifu Kö" and repeated on the first of two Torii tombstones, can only be accepted with caution. According to the birthdates in the above record, Kiyomoto (Kiyonobu's father) would have been twenty years old and his wife a mere eight years old in 1664. The discrepancy seems to suggest an adoption, but positive proof must await further research.

The "Torii ga Keifu Kö" states that Kiyonobu was born in 1664, was married in 1693 to a woman born in 1675 who bore him three sons and one daughter (or as Inoue suggests, four sons and two daughters). Accepting these dates and working backwards from the date of the first Kiyomasu-signed print known to Inoue, 1714, the likely date of birth of Kiyonobu's first (or second) son, i.e., Kiyomasu I, would be in 1696 at the latest in order to be old enough to have produced high-quality art in 1714. Such an approach reveals a rather arbitrary reasoning, but this characterizes the quality of scholarship on the Torii in general. Moreover, Inoue did not uncover any prints signed Kiyomasu dated or assigned between the sixth month of 1716 and 1724. Speculating that Kiyomasu might have died early, he then connected him with the inscription "Issan Domu" and the burial date 1716, both appearing on the left side of the earlier of the two Torii family tombstones. Inoue theorized that Kiyomasu I, as a son of Kiyonobu I, emerged in the artistic world in 1714 and died two years later. The prints signed Kiyomasu appearing after 1724 were, according to him, perhaps done by Kiyomasu II who was the adopted son of Kiyonobu I. Kiyonobu's second son was to become Kiyonobu II about the same time. Moreover, Inoue suggests that the true founder of the Torii school was not Torii Shobei Kiyonobu, but his father, Torii Kiyomoto. Thus, Inoue's genealogical construction is as follows:

Theory II.

In 1924 the German scholar, Fritz Rumpf, disagreed with Inoue, setting forth his belief that the first Kiyonobu and first Kiyomasu were one and the same person, and that the son of this artist continued to use both names after his father's retirement.(14) This theory conformed with the traditional genealogical ordering and was based primarily on the evidence of certain prints that were sealed "Kiyomasu" but signed "Kiyonobu," and was bolstered by certain stylistic similarities and parallels. Rumpf's judgment, however, has not found support among critics, most of whom are able to distinguish the hands of two distinct personalities in Torii works that can be dated before 1720. Rumpf's hypothesis also assumes the simultaneous use of two artist names based on the same stem "Kiyo", a procedure that has no known precedent. It should be noted that Rumpf's view has never been taken very seriously in Japan.

Theory III.

Our theory involves the opinion that Kiyomasu I was a younger brother of Kiyonobu I and not a son. The earliest reference in the West to the identification of Kiyomasu with a hypothetical younger brother of Kiyonobu was made by Dr. Julius Kurth. He based his conclusion on a theater program dated inaccurately to 1695, the date of Kiyonobu's marriage. Dr. Kurth offered no additional evidence.(15) Recently Dr. Richard Lane advanced the same theory.(16) He based his opinion on the discovery of the novel "Koshoku Tsuye Komuso" by Torindo Chomaro, which, with illustrations presumed to be by Kiyomasu I, is located in the Ryerson Library of the Art Institute of Chicago. The colophon of this book bears the signature Kiyomasu and is dated 1696. Recent research proved that the signature is spurious, however, and the book is now generally placed in the Hishikawa oeuvre. Dr. Lane offered no other recorded evidence to support his claim of a younger brother.

Theory IV.

In 1965, we determined to re-examine all the available evidence on the Torii school in an attempt to reach a more tenable solution than those that have been offered in the past. In making this study, we were forced to depend on aids which we knew or suspected to be very inadequate -- some of the same aids used by Inoue Kazuo in his monumental research. Scanty survival of works from this period, and the demonstrated unreliability of information reported in burial and family records required an attitude of unrelenting skepticism. Indeed, since 1923, the time of Inoue's works, a devastating war has destroyed any burial documentation of Höjöji (temple) that might have yielded some additional information. Despite this setback, it was possible to uncover two new "documents": one, and "ukiyö-zöshi" dated 1709, and the other, a recent Torii "Kakochö" (burial record) kept at Tokyo's Myoken-ji. This "Kakochö" was copied by an unknown transcriber from the Torii household "Kakochö", which in turn had been copied in the late Edo period by Saitö Chöhachi (Torii Kiyomine II) from the original temple record. Therefore, the results of our inquiry should never be regarded incontrovertible, suffering from the same lack of positive facts and reliable documentation that hindered Inoue's effort. The summary to be offered here then should be regarded as a kind of work in progress. The trend of available data suggested to me the following genealogical identifications, ones considerably different from those offered in the orthodox genealogy.

1. Torii Kiyomoto, Founder of the Torii school.

2. Torii Shobei Kiyonobu, first or second son.

3. Torii Kiyomasu I, first son of Torii Kiyonobu I.

4. Torii Kiyomasu II, adopted son of Torii Kiyonobu I.

5. Torii Kiyonobu II, second son of Torii Kiyonobu I.

Both the "Ukiyo-e Ruikö" edition of the "Torii ga Keifu Kö" were set down at some distance from the events in question, and therefore suffer from many unreliable additions and omissions.(11) The "Torii ga Keifu Kö" makes no distinction between first and second generation Kiyonobu and Kiyomasu, suggesting that the reference, Kiyomoto first, Kiyonobu second, and Kiyomasu third, is more an artistic genealogy than a family genealogy in the truest sense.(12) Moreover, prints definitely attributable to the first Kiyomasu have been uncovered between 1716 and 1724 proving beyond any question that Kiyomasu I did not die in 1716. (See study material No. 12) We need not consider the thorny question as to whether the inscription "Issan Domu" is or is not a posthumous name. There is a body of opinion, however, that this inscription is a Buddhist prayer and not a "Kaimyo" at all.(13) It also appears, based on certain dated prints, that there was a third Kiyonobu. We will discuss these problems at a later point in our review.

1. Torii Kiyotaka (dates unknown)

His name occurs in the "Koga Bikö" but his existence has never been confirmed by any surviving art or any contemporary record until our study. The 1709 edition of "Füryü Kagami ga Ike" indicated that Torii Kiyotaka was the veteran artist of the Torii and the teacher of Shobei.(17) (See study materials No. 13 and No. 14) His date of birth and death are unknown, as well as his genealogical relationship to the other members of the Torii school. This use of the term "veteran" (rohitsu) in the text reference may suggest that he was considerably older than the other members of the Torii family and as such the true founder of the Torii school. This contemporaneous reference then opens up an entirely new line of investigation. Moreover, postulating a Torii artist before Kiyomoto might help explain the family's move to Edo from Kamigata, their interest in Kabuki art after their arrival, and the emergence of a fully developed style of Torii art with no apparent antecedents. Unfortunately, no singed art by Kiyotaka is known to survive today. Although the precise description suggests a style not unlike that of Kiyomasu I.

2. Torii Kiyomoto

This actor-artist from Osaka had two sons and one daughter. His sons carried on the tradition of designing posters, programs, and single-sheets for the Edo-period Kabuki stage. The "Torii ga Keifu Kö" connects his name with the "Kaimyö" "ritetsu", and the dates 1645-1702, but because of a discrepancy in the dates for his wife and the fact that the original tombstones apparently did not confirm the dates, the entire identification is suspect. We have uncovered no extra art by Kiyomoto.

3. Torii Shöbei Kiyonobu I (b. 1664, d. 1729)

This artist was the second son (possibly adopted through marriage in 1693) of Torii Kiyomoto. Because of his great popularity he became the titular head of the Torii school. The earliest surviving art generally attributed to him is a medium-size novel (ukiyo-zöshi) titled "Iro no some Ginu", published in Edo in August of 1687. (See study materials No. 1) It bears in one edition, possibly the first edition, the colophon signature "Yamato eshi Shöbei zu".(18) The work is suspect, however, since the illustrations reveal nothing of the Torii style that emerged in the later Genroku period. What is detectable instead is the strong Hishikawa influence, which is characteristic of most book illustrations of the day, combined with certain Tosa characteristics. Moreover, the style of art suggests a mature painter of long experience and not a young student. This talent is quite evident in the highly sophisticated and delicate rendering of landscape details. Such sophistication of detail detected cannot be in the next signed works of Shobei appearing nine years later in 1697, which are unquestionably the art of Torii Kiyonobu and bear the Torii name in the signature. Indeed, on stylistic grounds, "Iro No some Ginu" seems to be the work of an entirely different master using the Shöbei name.(19) It should be noted that Shöbei is a personal name, and while utilizing the same first character "Shö" that occurs in Shöshichi (the personal name of Kiyomoto), it need not refer to only Torii Shöbei Kiyonobu I. All this in combination with the nine year time lapse between dated works provides an anomaly that keeps open the possible identity of this early Shöbei.

Kiyonobu's first signed and dated works, illustrated books, appeared in 1697; namely, "Honchö Ni jushi Kö", signed in the colophon "Eshi Torii Shöbei", and "Köshoku Daifuku-chö", signed in the colophon "Torii Shöbei 'ga'".(20) Both contain art of surprisingly poor quality, revealing only occasional glimpses of the mature Torii style that other works of the same date indicate as proper for this time. The figures and landscape are poorly drawn, the overall compositions weak, and the artistic conception limited. In landscape detail, these works are definitely inferior to the earlier "Iro no some Ginu", suggesting here an artist of less maturity. Kiyonobu's first major works in the fully developed Torii style do not occur until 1700, first his great "Füryü Shihö Byobü" series, followed shortly by the collection of Yoshiwara beauties titled "Keisei Ehon", which is now housed in the Ryerson Collection. (See study materials No. 3 and No. 4) In the former we encounter the Torii style conventions used for actors in vigorous action (e.g. the "hyötan-ashi" and "mimizu-gaki" characters), and in the latter, the typical "bijin" renderings of solitary women, gorgeously clad, with the distinct Torii face-type that is almost devoid of emotion. This style was to serve as a basis for the numerous examples in painting and print of the Kaigetsudö school "bijin". Both styles can be traced back to unsigned dated "eiri-kyogen-bon" of 1697 and 1698, works of great historical importance to the history of the Torii school. (See the biographical and art discussion for Kiyomasu I for further discussion of these early books).

Research by: Howard A. Link.

Person TypeIndividual

Terms