Katsushika Hokusai / Katsukawa Shunrō / Katsushika Taito / Kakō

Japanese, 1760–1849

CountryJapan

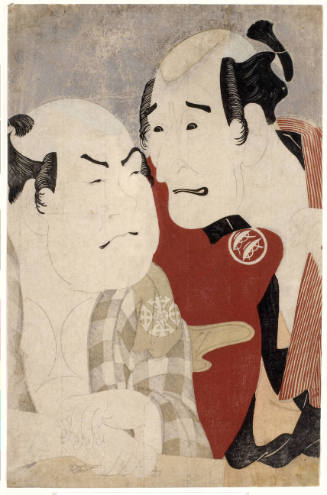

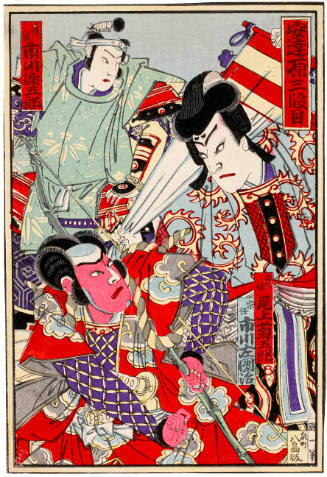

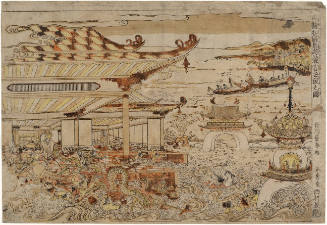

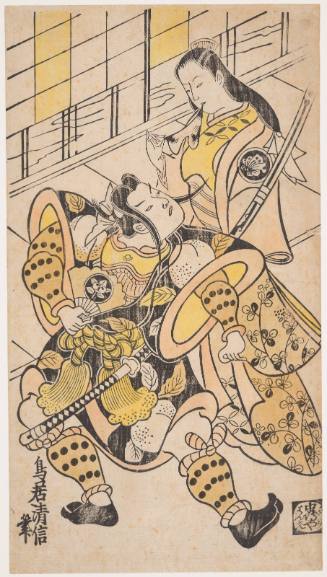

BiographyKatsushika Hokusai, with his enormous imagination and diversity, has sometimes been hailed as the greatest of all Japanese print artists. This opinion is not without defense; Hokusai’s biography and artistic career are comparatively well documented. He is discussed in the Ukiyo-e Ruikö and related sources. Moreover, Dr. Muneshige Narazaki has made a thorough study of his career and biography in the monumental Hokusai Ron (1944), which remains the best single source on the artist’s work. Hokusai lived most of his life in the Edo business district along the Sumida River. In his teens he studied the art of woodblock engraving under the printer Honjo Yokozunachö. Thus knowledge, which required the mastery of copying an artist’s individual line, was to prove very important to his future artistic career.At the age of eighteen, Hokusai became the pupil of Katsukawa Shunshö (that great artist of Kabuki who helped to establish a more realistic portrait of the actor), and within one year he was given the art name Shunrö in recognition of his talent. The Michener assemblage includes a few choice prints signed Shunrö from the 1780s; especially choice is the middle sheet of a triptych depicting a Chinese matsuri (No. 94).

From 1778 to around 1788, he experimented in many facets of the wood block (i.e., bijin-ga, yakusha-e, kachö-e, uki-e and distinctive illustrations for novelettes). Hokusai was obviously searching for a style of his own, a quest that was periodic throughout his long life, for as he tired of one kind of expression he sought a new and fresh one. It is Hokusai’s unique probing quality that provides a wide variety of styles. His greatest individuality was also to be the source of considerable trouble. It was clearly impossible for young Hokusai to remain slavishly loyal to the style of his mentor, Shunshö, and criticism of Hokusai’s artistic experiments was often leveled by his seniors, Shun'ei and Shunkö.

After Shunshö's death in 1792, Hokusai began to produce works jointly with the artist Tsutsumi Törin (III), who claimed to have derived his style from that of Sesshü (Törin often signed his work Sesshü XIII). He experimented widely with prevailing styles: bird and flower studies of the Nampin School; literati style works of Chinese Ming painting; Japanese style pictures of the Sumiyoshi School; and end even Kanö style art. Perhaps due to his enthusiasm for a wide range of styles, Hokusai was finally expelled from the Katsukawa School in 1794.

His names form a vast and confusing study in themselves. It was traditional for artists to take a special artistic name, or gö, and sign their work. Hokusai was unusual among ukiyo-e artists, changing his name nearly a hundred times in the seventy years until his death in 1849. We know him today as “Hokusai” because this particular name appeared on and off, in various combinations, during a long period from about 1796 to 1833.

In 1795 he assumed the leadership of the so-called Tawaraya School, once headed by Söri (I) who died in 1780, and assumed the name Söri III for a time. But Hokusai’s adherence to the Tawaraya tradition of Rimpa painting was hardly exclusive, for among the subjects he depicted at this time were the more purely “ukiyo-e” series of bijin (beautiful woman) studies popularly known as Söri bijin-ga.

In 1798 Hokusai broke with the Tawaraya family and became an independent artist. For the next thirty years this unsettled master-produced prints of power and originality under a bewildering variety of names. A number of these works are represented in the Michener Collection. For example, in the 1830s Hokusai produced a series of at least ten chüban bird and flower studies showing a strong influence of Chinese painting. The Michener Collection owns one example published by Eijudö in virtually mint condition depicting a bullfinch and drooping cherry branch set against a stunning blue background. The remainder of the series in the Academy, unfortunately, has been determined to be later recuts and not part of Hokusai’s genuine oeuvre.

Next to the “Thirty-six views of Mt. Fuji,” the eight-print series, “Tour of the Falls of the Various Provinces” (Shokoku Taki Meguri) must be regarded as the boldest and most original of Hokusai’s pure landscapes. Indeed, as the Hokusai specialist Peter Morse suggests, “... In its unique combination of real and fantastic elements, it may surpass even the ‘Fuji’ set in its consistently high standard.” The Academy assemblage owns seven out of eight prints of this series, all in good condition.

Nonetheless imaginative, even though depicting actual places in Japan, is the eleven-print series “Guide to Famous Bridges of the Various Provinces” (Shokoku Meikyo Kiran), probably published in 1834 by Eijudö. The Michener Collection has eight pristine prints from this important series.

According to the recent research of Mr. Roger Keyes and Mr. Morse, a total of eight prints have been recorded in the series, “Guide to Famous Places” (Shökei Kiran), possible published in 1835. This exceptionally rare set, in fan print format (uchiwa-e), is represented by four excellently preserved examples in the Collection.

The assemblage also boasts the series, “The Hundred Poems Explained by the Nurse,” which represents both Hokusai’s last years of life and ability as a humorist. Before, all but one print from the series had been assembled, and this year the Academy was fortunate in locating the missing sheet, making the group the only complete series known in the world.

-----

(Taken from catalog index cards)

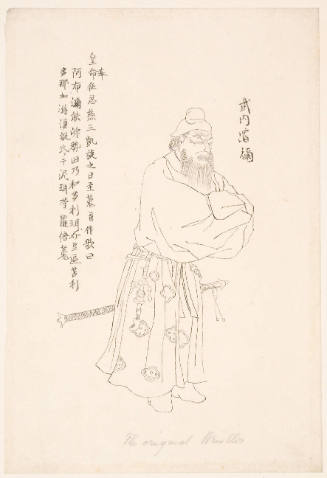

Shunrö (alias Hokusai) was the heretical pupil of the Katsukawa Shunshö whose style he emulated until creativity overpowered is loyalty to the school. It would be instructive for the student of ukiyo-e to realize that ukiyo-e artists often utilized alternate art names. The case of Katsushika Hokusai is an extreme example, but well worth considering here. Hokusai's original surname may have been Kawamura, but early sources also indicate that he was adopted into the Nakajima family, hereditary mirror makers to the shogun. From the age of 14 his personal names included Tokitaro, Tesuzo, and later in life, Miuraya Hachiemon (when forced into self-exile). His art names are as follows: Katsukawa Shunrö (before 1780); Zeiwasai (1781); Tokitaro and Tetsuzo (1780-1785) found in sumizuri-e books; Mugura Shunrö (1785) and Gunbatei (1785); Hishikawa Söri (1787); Tawaraya Sori, Hiakurinsai Sori, and in the preface to a book, Katsushika Sori (early 1790s); Toshu Shunrö (mid-1790s, according to Hirano); Hyakunin Sori (1796); Hokusai (by 1797, but some say not before 1799); Kako (by 1800); Gakojin, Tokimasa, Hokusai Shinsei (1800); Kintaisha (1804); Gakiojin Hokusai, Gakyo Rojin, Kukusing (1805); Toyo, Katsushika Hokusai (1806); Manui-hitsu (1808); Taito (1811); Zen Hokusai Iitsu (1817); Tameichi (by 1820); Manrojin (1835); Gakio Rojin Manji (literally "old man mad about drawing", his last name).

Some scholars estimate that Hokusai utilized at least 28 more names for his novels and poetry, and for other purposes. From all this we learn that Shunro's main activity occurred before 1780, although some prints with this signature appear to be the product of the 1790s based on their Sharaku-like style. Apparently Hokusai used several different names within any given time, if we are to judge by the dating of prints to the same year with differing signatures. In the earliest period, his art follows closely the style of Shunshö and Shunkö but his art also shows elements that we associate with the Sharaku style. In the 1780s he had been friendly with the Ösaka Kabuki artist, Ryükosai. Shunrö's association with the Kanö artist Yusen led to his final expulsion officially in 1795.

Hokusai, with his enormous imagination and diversity, may well be the greatest of all Japanese print artists. This opinion is, at the least, easily defended. Certainly Hokusai was the first of all Japanese artists to be widely appreciated in the Western world. Peter Morse and Roger Keyes of San Francisco are collaborating on a complete catalogue raisonne of all of Hokusai's prints, probably numbering over two thousand. Much evidence remains to be discovered or confirmed, and it may take many years for much of the information given here to be verified.

Hokusai lived to the age of 90, by Japanese calculation. He was born in 1760 in the lower-class Honjo district of Tokyo (then called Edo), the adopted son of a mirror-maker, Nakajima Ise. The artist's original name seems to have been Nakajima Tokitaro. His names form a vast and confusing study in themselves. It was traditional for artists to take a special artistic name, or "gö", to sign their work. Hokusai was unusual among ukiyo-e artists, changing his name nearly a hundred times over seventy creative years, until his death in 1849. We know him today as "Hokusai" because this particular name appeared on and off, in various combinations, during a long period from about 1796 to 1833. The name means simply "North Studio."

As a boy, it is said, he went to work in a book-lender's shop. Next, he was apprenticed to a block-cutter, learning the technical aspects of printmaking. At the age of 18, he became a pupil of the great artist, Shunshö, head of the Katsukawa school of artists. At this time he took the name "Shunrö", the first under which he became well-known as an artist. He developed slowly, doing actor prints and book illustrations in the Katsukawa style. It can fairly be said that if Hokusai had died at the age of 37, he would be known today only as a minor and subsidiary artist -- and the history of both Japanese and Western art would have been quite different.

From 1791 to 1822, he began to produce prints of real power and originality, under a bewildering variety of names. At the age of 63, Hokusai is believed to have begun his most famous series of prints, the "36 Views of Fuji".

The "Eight Views of the Ryukyus" are a traditional group of subjects used for depicting various places in Japan; however, Hokusai may have been the first to apply the formula to the distant and somewhat foreign Ryukyus. It has recently been discovered that Hokusai, who apparently never visited the Ryukyus, took his basic compositions from an illustrated history book entitled "Ryukyu Kokushiryaku". The only date known so far for that source book is 1831.

Hokusai's biography and artistic career are comparatively well-documented. He is discussed in the "Ukiyo-e Ruikö" and related sources. Moreover, the Ukiyo-e scholar, Narazaki Muneshige, has made a thorough study of his career and biography in the monumental "Hokusai Ron" (d. 1944) which still remains the best single source on the artist's works. Hokusai lived most of his life in Edo in a business district along the Sumida River. He was born in the Katsushika district of Edo, Katsushika later being his adopted artistic surname. His father was called Kawamura, but because of Hokusai's early adoption at the age of 3, many sources merely list his step-father, Nakajima Ise, who was official polisher of mirrors to the Shogunate. This was not to be the case for Hokusai, however, for at an early age he showed a keen interest in the graphic arts. Apocryphal stories abound of Hokusai's youth and achievements. One story indicates that he left home and his family profession at an early age, preferring to work for a lending library to the tedious chores of polishing mirrors. If this is true, he apparently continued to use the name Nakajima for his entire life; documents from a later period survive in which he used this surname.

In his teens, Hokusai studied the art of woodblock engraving under the printer Honjo Yokozunachö. This knowledge, which required the mastery of copying an artist's individual line, was to prove very important to his future artistic career.

At the age of 18, he became a pupil of Katsukawa Shunchö (that great artist of Kabuki who helped to establish a more realistic portrait of the actor) and within one year he was given the art name "Shunrö" in recognition of his great talent.

From 1778 to around 1788, he experimented in many facets of the woodblock (i.e., "bijin", "yakucha-e", "kocho-e", "uki-e", and distinctive illustration for novelettes). Hokusai was obviously searching for a style of his own -- a quest that was periodically to occur throughout his long life, as he tired of one kind of expression and sought a new and fresh one. It is Hokusai's unique probing quality that provides for a wide variety of styles (the critic who insists on defining Hokusai's style on the basis of his later landscapes is overlooking the very nature of this searching genius). His great individuality was also to be the source of considerable trouble. It was clearly impossible for young Hokusai to remain slavishly loyal to the style of his mentor Shunshö, and criticism of Hokusai's artistic experiments were often leveled by his seniors, Shun'ei and Shunkö.

After Shunshö's death in 1792, Hokusai became increasingly dissatisfied with the traditional Katsukawa formula. He began to produce works jointly with the artist Tsutsumi Törin (III) who claimed to have derived his style from that of Sesshü (Törin often signed his work Sesshü XIII). Other experiments in "style shopping" included: bird and flower studies of the Nampin School; literati-style works of Chinese Ming painting; Japanese-style pictures of the Sumiyoshi School, and even Kanö-style art. Perhaps due to this rather unstable "eclecticism" Hokusai was finally expelled from the Katsukawa School in 1794 -- "the very year," notes Dr. Narazaki Muneshige, "that the work of another great print artist, Sharaku, suddenly and apparently without any warning burst on the ukiyo-e scene in full maturity."

It wasn't until mid-1795 that the thread of Hokusai's artistic activities becomes again clear. At this time he acquired a higher status in artistic circles than he had ever held previously by assuming leadership of the so-called "Tawaraya" School. This school carried on the traditions of Sötatsu and Korin (e.g., Rimpa School) and had its immediate origins with the artist Sennyoshi Hiroyuki, who adopted the name Tawarayu Söri I when he revived the "Rimpa" traditions. Söri I had died in 1780, and no one had yet succeeded him by 1795. A young untrained artist, Söji, was named to follow Söri, but because of his youth, it was arranged to have Hokusai temporarily assume the Söri name and train young Söji for the day when he would be worthy of the Söri designation.

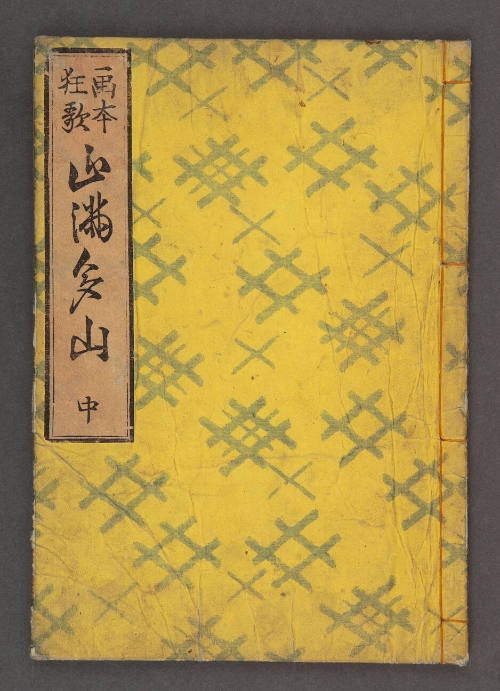

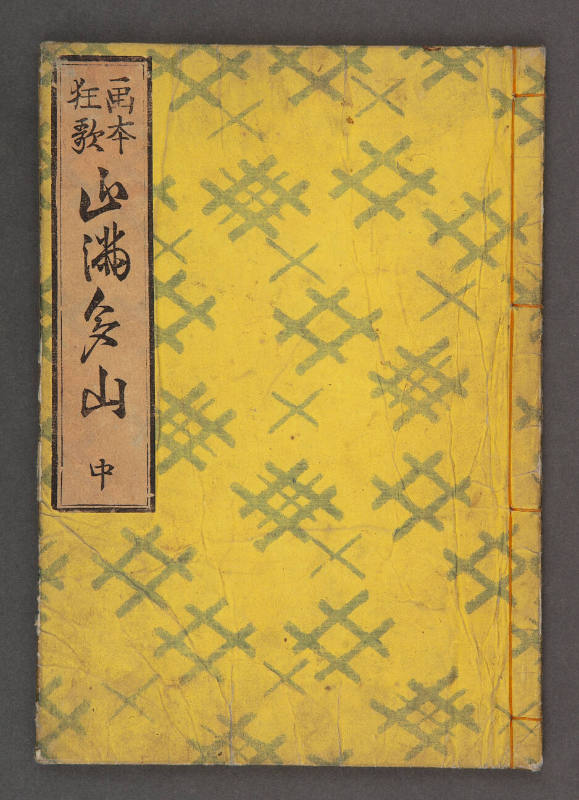

Hokusai's adherence to the Sötatsu/Korin tradition of painting was hardly slavish. Among his more purely "ukiyo-e" subjects was a series of "bijin" (beautiful woman) studies of great charm, which became popularly known as the "Söri bijin-ga"; some satirical illustrations for the humorous "Kyoka ehon"; and some finely detailed landscape studies showing Chinese painting influence.

Four years later in 1798, Hokusai broke with the Tawaraya family, returned the Söri name to Söji, and became an independent artist. For the next 30 years or so, Hokusai was to steadily develop in his art. Indeed, Dr. Narazaki Muneshige, the great Hokusai scholar, believes that his most significant work occurs in these years. Dr. Narazaki summarizes Hokusai's contributions with the following points:

1. Creative use of Western techniques in landscape.

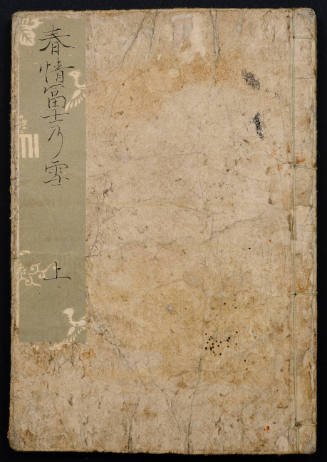

2. High quality lyrical illustrations for "Kyöka-bon" (poetry books).

3. Illustrations characteristically detailed and totally brilliant in Yomihon (illustrated novelettes).

4. Sensuous charm in his paintings of beautiful women.

5. Astonishing mastery in portraying human figures in everyday life.

6. Diversity and invention in landscape and "bird and flower" themes.

All these efforts crystallized into one single creative effort when, in 1823, he produced his greatest of all masterpieces, "36 Views of Mt. Fuji".

Hokusai probably knew great financial success during these years; he had around 20 or 30 disciples. From the anecdotes that tradition has left us, however, we learn that he was perennially poor and indifferent to worldly affairs, and that he had changed his dwelling 93 times in all to avoid payment of debts. Moreover, his list of artistic names number in the 30s -- each one accompanied by a slightly different style. Of course, many of the more fanciful anecdotes are totally apocryphal making it difficult to determine the extent of Hokusai's actual eccentricities. Nevertheless, all these tales testify to a powerful personality who no doubt was truly indifferent to all save his art.

Following his success with "36 Views of Mt. Fuji" he completed his "Unusual Bridge" series, his "Waterfall" series, and his "Scenes of the Ryukus" -- all highly inventive works.

In 1833, Hiroshige's "53 Stations on the Tökaidö" became the rage of all Edo, and Hokusai was immediately over-shadowed in the eyes of the fickle public. In an attempt perhaps to meet Hiroshige's challenge, Hokusai produced his 3 volume black and white book, "100 Views of Mt. Fuji", and although the volumes include some very fine work, it failed to restore Hokusai to his unchallenged position.

He died in 1849, a bitter, rejected man who only asked for more time to become a "real" artist. "History has been kinder to Hokusai than the public of Edo," Dr. Narazaki notes. "It has shown that there is room enough in Japanese art for both Hokusai -and- Hiroshige."

FUKAKU SANJÜ ROKKEI (Thirty-Six Views of Mt. Fuji)

This famous series of 46 prints was published by Eijudö sometime between 1823 and 1831. Originally conceived as a series of 36 prints, ten more were added in 1831, thus accounting for the erroneous title. It is speculated that Hokusai may have even intended to continue the series. Indeed, he later produced a three-volume set of "100 Views of Mt. Fuji" but in black and white. Since the prints are not numbered, the ordering of the designs in catalogues vary. A tentative attempt is made here to organize the prints according to date and impression, dividing the material into three groups.

Group I consists of 10 subjects all with the signature "Hokusai Aratame I-itsu hitsu" and a key block line printed in blue. The publisher's mark is omitted. Prints printed with a black key block line, but with the same signature are late "Group I" impressions. Only a few such prints are known.

Group II is another group of prints utilizing the signature, "Zen Hokusai I-itsu hitsu", and is also printed in a blue key block line. Occasionally impressions in the blue-line group will include a publisher seal. These impressions (usually restricted to one or two colors) invariably appear to be earlier than those which omit the seal and are printed in three or more colors. The monochromatic is perhaps inspired by a fashion for "azuri-e" prints in the mid-1820s. Sometimes, this "azuri-e" tradition will be repeated in a late edition but in these cases the publisher seal will be omitted. Prints printed with a black key block line but with the same signature are late "Group II" impressions.

Group III, the last 10 prints and datable to 1831, are those signed "Zen Hokusai I-itsu hitsu" printed in a black key block line only. It is possible that the blocks of Group I and II were re-used at this time, thus accounting for the late impressions, all in black line, which survive.

- - - - - - -

HOKUSAI'S "GOMAI"

Hokusai Names Seen on Prints:

Katsukawa Shunro

Katsu Shunro

Shunro

Shunro aratame Gunmatei

Gunmatei

Kako

Hyakurin Sori

Sori

Sori aratame Hokusai

Sori aratame Hokusai Tatsumasa

Hokusai Sori

Hokusai Sori Shinya no Mushi

Oju Hokusai Sori Seikijo

Saki no Sori Hokusai

Hokusai

Hokusai Sensei

Gakyojin Hokusai

Gakyojin Hokusai Rofu

Toyo Dokurin Gakyojin Hokusai

Kyobashi Gakyojin Hokusai

Other Names in Books (Hiller and Toda):

Tokitaro

Zewasai (as author)

Hakusanjin Kako

Tokitaro Kako

Sori aratame Hokusai Shinsei

Hokusai Shinsei

Hokusai aratame Katsushika Taito

Katsushika Zen Hokusai Iitsu

Jugasei Katsushika Hokusai

Zen Hokusai Katsushika Iitsu

Hokusai Rojin

Iitsu

Katsushika Zen Hokusai Teitsu Rojin

Zen Hokusai Iitsu Rojin

Zen Iitsu Rojin

Zen Hokusai Manji Rojin

Zen Hokusai aratame Gakyorojin Manji

Gakyo Manji Rojin

Toyo Hokusai

Kyukyushin Hokusai

Katsushika Hokusai

Katsushika Rohu Gakyojin Hokusai

Hokusai aratame Taito

Taito

Hokusai Taito

Zen Hokusai Taito

Hokusai aratame Iitsu

Hokusai aratame Katsushika Iitsu

Hokusai Taito aratame Katsushika Iitsu

Katsushika Iitsu

Katsushika no Oyaji Iitsu

Katsushika Rojin Iitsu

Fusenkyo Iitsu

Getchi Rojin Iitsu

Zen Hokusai Iitsu

Ro Iitsu

Gakyorojin Hokusai

Zen Hokusai

Hokusai aratame Gakyorojin Manji

Gakyorojin Manji

Zen Hokusai Manji

Manji

Manji Rojin

Hokusai Manji Rojin

Katsushika Manji Rojin Hachiemon

Zen Hokusai Manji-o

Katsushika Rojin Manji

NB: Tameichi, Tamekazu, and Tamekadzu are all thought misreadings of "Iitsu".

NB: Gunbatei and Gummatei are believed to be misreadings of "Gunmatei".

NB: Tesuzo or Tetsuzo is said to have been his name as a block-cutter.

NB: Signatures known on paintings are not listed.

Total: 67 "go" (so far).

Research by: Howard A. Link.

Person TypeIndividual

Terms