Utagawa Toyokuni I

Toyokuni was an ukiyo-e painter, print artist and illustrator who has been criticized for being the least original of all the leading artists of the ukiyo-e school. Yet apparently succeeded so well in emulating the style of his contemporaries that he has been universally accorded a place nearly equal to the most creative artists of his day.

Toyokuni became a pupil of Utagawa toyoharu at the age of thirteen or fourteen and was quick to adopt the style of his mentor. Around 1786, he began to illustrate ki-byoshi (yellow-cover books of humorous satirical fiction) and by 1791 had already designed a pleasing triptych in which he utilized his teacher’s fondness for western perspective.

Toyokuni’s borrowings were not altogether sequential. He did not move from the stylistic orbit of one artist to another as has often been stated. Frequently he would return to the style associated with an earlier master if it served his purpose. This fact offers support for the growing opinion that Toyokuni was not an ecclectic borrower any more than a number of other ukiyo-e masters of the day who have escaped such critical censor. A new image of Toyokuni is emerging from the evidence that suggests a hard-working artist who possessed a versatile brush capable of creating with equal skill works of art in a number of different manners to satisfy the needs of the public.

Students of ukiyo-e have come to associate a given style with the artist that best represented this style. There are, for example, the tall sedate figures of Kiyonaga, the willowy erotic figures of Utamaro, the lyrical child-like figures of Harunobu, and the intensely penetrating portraits of Sharaku. When confronted with an artist’s works that has qualities that have come to be equated with one of these key masters, his art is regarded as derivative. In the case of Toyokuni, some of his prints may in fact predate the supposed source. What has been lacking in the study of Toyokuni is a more accurate method of dating.

Such a method was recently suggested in the work of Sadao Kikuchi, a retired curator of Japanese art at the Tokyo National Museum and Keeper of the Matsukata Collection of Ukiyo-e. Noting that systematic ukiyo-e research has been greatly enhanced by the study of dated illustrated books, where the faithful in calligraphic signature can be observed in colophon, Kikuchi made special study of Toyokuni’s signature in actor prints. since such prints can be dated with a fair degree of accuracy on the basis of kabuki evidence, Kukuchi arranged his actor studies chronologically, producing a year-by-year study of Toyokuni’s signature and its subtle changes. This classified collection of signatures is reproduced in the ALSO reference of this database for easy reference. Comparison made with the signatures iof the printsselected for inclusion in this database has resulted in a tentative ordering. The changes in style that can be observed, while never inclusive, seem to adhere to the following basic sequence.

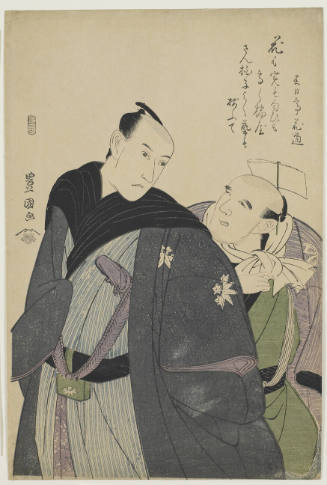

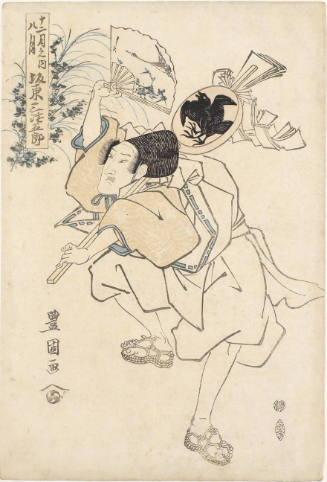

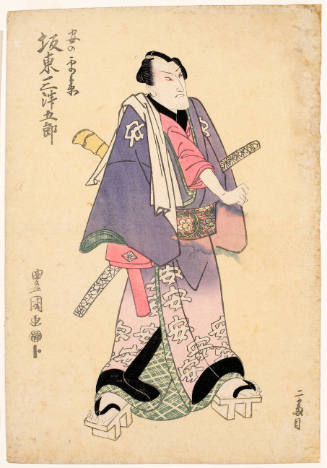

His art of the early 1790s follows the style associated with four important contemporaries-Katsukawa Shunshô (1729-1792), Katsukawa Shun-ei (1762-1819), Torii Kiyonaga (1752-1815) and Kitao Shigemasa (1739-1820). In his nigao-e (likeness portraits), done in the wake of Shunshô, one realizes his genius in exhibiting good taste and fine color. Such prints are a sheet delight. But as early as 1794, he was working in the same manner as Shun-ei’s “invention” of large head portraits achieving excellent results also. The date of Toyokuni’s first attempts at making facial likenesses is reported by Suzuki(Okamoto, et. al., Kabuki, 1990, p.25). “The date of Toyokuni’s first attempts of making Facial Likenesses, (nigao-e) can be told from the preface of a comic illustrated novel (kiyôshi) of the fifth year of Kansei (1793) entitled Tengu tsubune nanna no Edokko (The Goblin Stones and the Man from Edo with the Nose) This book includes the phrase: nigao eshi Toyokuni (Toyokuni the facial likeness master).” This evidence proves that Toyokuni had already gained fame for his likeness portraits as early as 1793, no doubt due to his friendship with Shun-ei.

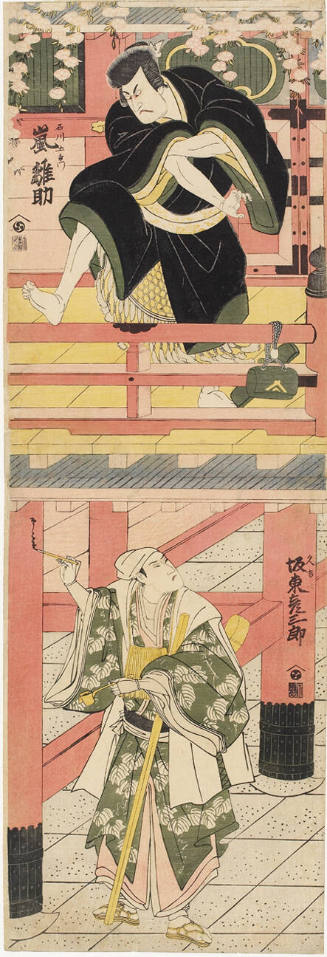

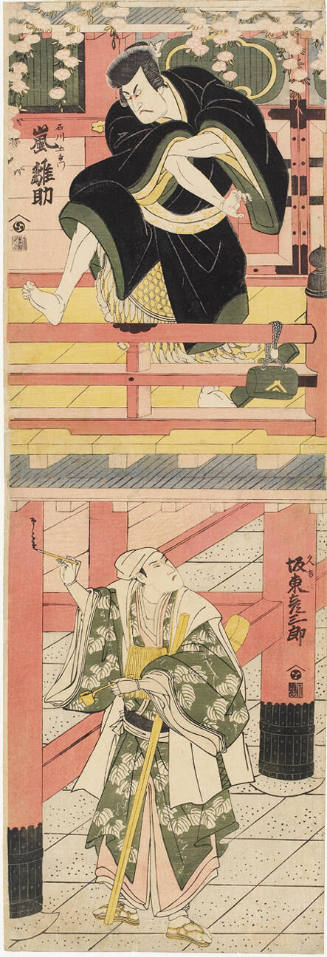

The cyclonic force of Sharaku is often cited as having influence toyokuni’s superb series of at least forty actor portraits, titled, View of Actors on Stage, but some of the portraits can be dated before Sharaku struck Edo with such visual and psychological force. The series seems more directly influenced by Shun-ei and owes little to Sharaku in my opinion. Suzuki, ibid. p25 describes the series as follows: “This series, with its slightly aestheticised portrayals of the actors and its crisp, clear delineations, transmits splendidly to the viewer the fun of kabuki...records confirm the immediate success of the series. Many of Toyokuni’s subjectsare the same as those of Sharaku, and it appears that the two artists were rivals of some sort, but Toyokuni ultimately won out.”

It is in Toyokuni’s work dating from 1797-1800 that we find the exaggerated conventions of Sharaku invading his art. Indeed it is this style which made the author of Ukiyo-Ruikô disclaim his art with the comment “(He) makes ôkubi-e in a style imitating that of his pupil Kunimasa.” Actually both artists were following the earlier portraits of that towering genius Sharaku, but only Toyokuni was censored for it. It is these very portraits that the ukiyo-e expert, Suzuki Jûzo has admired Toyokuni with these words: “...he took the close-up actor portrait to its highest form...”

Kitagawa Utamaro (1754-1806) and his followers exerted the strongest and most profound influence on toyokuni’s beautiful women studies. Utamaro’s great half-length figures are challenged in 1794 by Toyokuni’s superb series of beauties in the same format. Utamaro’s greatest triptychs are matched by at least five fresh toyokuni triptychs that must be judged as outstanding.

Toyokuni’s career after 1800 is envisioned by critics as one of total debasement. the decline is based on the development of the iki style of literalism in the depiction of courtesans and actors as opposed to the idealism of earlier periods. this style has come to be admired in Japan, and even emulated by pop artists working in Japan and in the West.

Perhaps Toyokuni, instead of being admonished for his efforts, should be admired for his tenacity and courage to continue to work into the tumultuous changes of the 19th century. These changes included a greater realism and polish in kabuki, which in turn had an important effect on the print; it gave rise to the highly realistic ki-zewamono (living-genre-plays) drawn from literary works not originally written for kabuki or bunraku. This change in turn produced a very marked evolution in the art of Toyokuni in an attempt to conform to the new taste. Instead of continuing to emphasize the individual characteristics of actors he developed instead a new mannerism--- the so-called iki style... Add to this the dramatic increase in demand for actor prints and bijin studies, along with the short-cut formula techniques of sloppy publishers, and you have an equation for artistic decline.

Toyokuni’s great inventiveness never completely disappeared, however. His numerous textbooks for beginners showing how to draw portraits of actors, his prodies on famous townsmen with likenesses of kabuki matanee idols, his vertical polytichs intended to impart a three-dimensionality to the compositio, and the introduction of the death portrait (shin-e) to ukiyo-e are among Toyokuni’s innovations intended to stimulate or renew interest in kabuki and the “ukiyo” world. Toyokuni was much more of a success story than posterity has credited him.