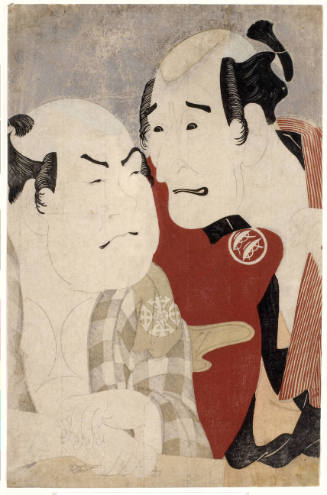

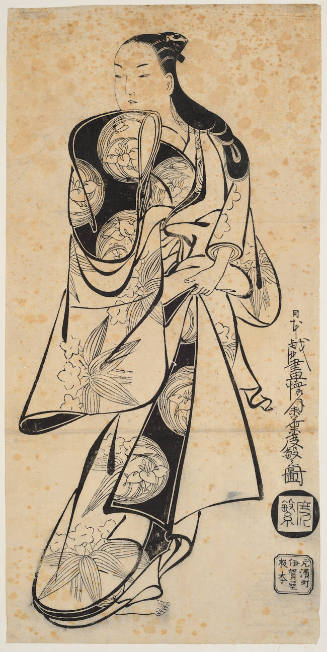

Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Japanese, 1797 - 1861

CountryJapan

BiographyA late edition of the "Ukiyo-e Ruikô" (1880) indicates that Utagawa Kuniyoshi was born on the first day of 1798 at Nihonbashi in Edo (now Tokyo). A monograph published in 1894 on the Utagawa school, Utagawa Retsuden, provides details as to his real name and the fact that his father was a dyer of fabrics, from which he may have developed an early sense of design and patterning. Some vague stories about his childhood suggest an early interest in art, but those rumors have never been confirmed. Early scholarly treatises (e.g., "Ukiyo-e Nempyô" and the "Ukiyo-e Shiden") agree that he became a pupil of Utagawa Toyokuni I in 1811, but this statement is unconfirmed by contemporary evidence. His earliest known surviving work, and illustrated novelette dealing with the famed vendetta, Chûshingura, is dated 1814, but since no honorific preface is made by Toyokuni in the colophon of the book to introduce his first pupil, it is probably *not* his first work.Kuniyoshi was obviously an eccentric. Near contemporary comments say, “He was of such a wild, unbridled disposition that even his relatives turned their backs on him ... he was often short of tuition fees and had to eat at the house of his fellow pupil and senior, Kuninao.”

For about two years (1814-1816) a steady flow of work was published by Kuniyoshi. Unfortunately, most of it gives little evidence of his great talent and it is perhaps this fact that discouraged publishers from commissioning Kuniyoshi for future print designs. According to the Ukiyo-e scholar, Suzuki Jûzô, who has made a careful survey of Kuniyoshi’s surviving art, all orders from publishers ceased by 1817. An earlier account indicates that during the 1820s, poverty forced Kuniyoshi to work as a hawker. The rivalry between Kuniyoshi and Kunisada supposedly had its origin during this time. It is related in an anecdote that Kuniyoshi began to improve his art in order to outstrip Kunisada, who had achieved considerable success and recognition.

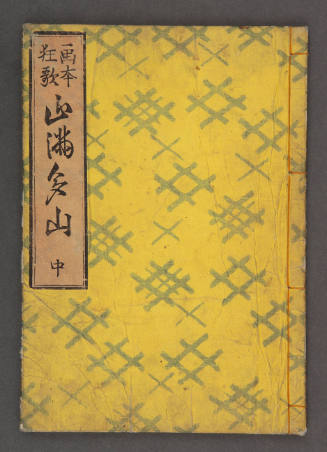

While such rivalry was possibly a factor, it was his acquaintance with the Kyôka poet, Ameya Kakuju, that helped Kuniyoshi find himself. This minor poet of the day gave him practical patronage and classical inspiration, but most importantly, he offered Kuniyoshi friendship and encouragement. This is borne out by the fact that Kuniyoshi’s first major success dealt with a Chinese classic on heroes, "Suikoden", adapted in Japanese by Bakin around 1827.

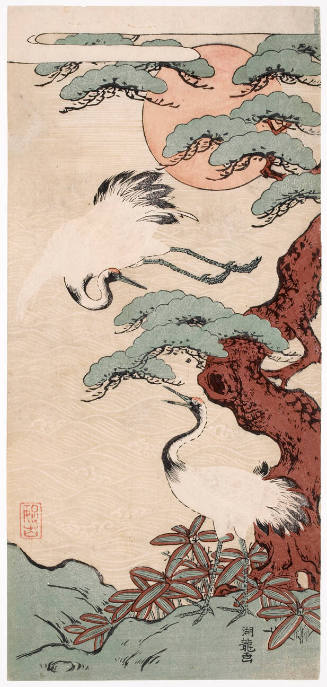

In 1825, Kuniyoshi adapted the Suikoden theme for a series dealing with courtesans in a typical “ukiyo-e” parody entitled "Keisei Suikoden". The format became a fad for the next few years and a number of important commissions resulted. All this helped secure Kuniyoshi’s reputation as an ukiyo-e artist of the first rank. While B.W. Robinson, Kuniyosh’s chief cataloguer in the West, regards the period of 1830-1843 (known in Japanese by the nengô, “Tempô”) as representative of Kuniyoshi’s mature years, I would rather look upon this thirteen-year span as one of remarkable innovation. First, Kuniyoshi published two important groups of prints in which he skillfully assimilated Western chiaroscuro technique into his own individual sense of form. His Tôtô Meisho series and the group of four prints with the prefix “Tôtô” testify to his ability to re-fashion Western techniques into something individual; the works contain some of his finest art.

It is during this time that the scope of Kuniyoshi's artistic activity widened. To compete with Hiroshige’s “Fifty-three Stations of Tôkaidô”, completed in 1834, Kuniyoshi produced a sparkling series of his own bearing the same title. Completed in twelve sheets, each print encompasses several stations and is full of sharply observed incidents of human interest set against panoramic landscapes of great variety. Along with these typically-Japanese landscapes, Kuniyoshi designed a most distinguished series dealing with the life of the 13th century Buddhist leader, Saint Nichiren, entitled "Koso Go Ichidai Ryaku Zu" (Abridged Illustrated Biography of Nichiren). While we admire the ingenuity of Kuniyoshi’s illustrations for this series, it should be mentioned that the material is not altogether original, for the master based his work on the picture book, "Bunpo Sansui Iko", published in 1824, with illustrations by the Kishi school artist, Kawamura Bunpo. Perhaps the most striking prints of the period are Kuniyoshi’s highly atmospheric "Tôto Omiyagashi no Zu" (Picture of Omiyagashi in the Eastern Capital) and his surrealistic depiction of Chûshingura, act 11. The latter deserves comment here. Known in the West by the popular title, “Night Attack of the Forty-Seven Rônin”, the master has combined European perspective, restrained color, and a strange atmospheric sky to convey in the words of Robinson, “A striking impression of the cold and silence of the deserted moonlit streets as the rônin go up the rope-ladder, one by one, over their enemy’s palace wall.” Comparing this highly personal design with his slightly later series dealing with the same play might prove disappointing. These later Chûshingura works, while not lacking in quality, revert to a basic Utagawa style and may be thought of as more purely Japanese.

Also during this time, Kuniyoshi produced his extraordinary series, "Hyakunin Isshü" (The Hundred Poets), with its many scenes of court life the Fuijwara period, blending literary illustration and genre landscape iwth exquisite results.

Japanese scholars suggest the mid-1830s for this work while cataloguers in the West date the series to just before the Tempô reform of 1842. Whatever the precise dating, it is clear that Kuniyoshi has relied upon earlier depictions, probably certain old Tosa school scrolls. This is suggested by the more restrained and aristocratic character of this very famous series. The close of the Tempô period witnessed Kuniyoshi’s most remarkable series, Nijûshiko Dôji Kagami (Mirror of the Twenty-Four Paragons of Filial Piety), in which he depended on European engraving for a "foreign" flavor to his illustrations of old Chinese legends. With such a diversified output as this, it is no wonder that his activities became famous and were even commemorated in frivolous comic poems. In the sixth month of Tempô 15 (July, 18423), a group of reforms were instituted by the insecure Tokugawa government outlawing aspects of the popular print. For Kuniyoshi’s art, the only visible sign of the decree was the appearance of a special group of censor’s seals, first one per sheet, but after 1847, always two seals per print. Kuniyoshi’s later years generally saw a return to a more purely Japanese subject and technique. For example, the master’s Tôto Fuji ni Sanjû rokkei (Thirty-Six Views of Fuji from the Eastern Capital), while not lacking in inspiration, shows only occasional European touches to remind the viewer of Kuniyoshi’s great innovations of the Tempô era.

His last great work -- a painting of an old hag -- is dated 1855 and reveals, once again, his ability at Western chiaroscuro. Soon after its completion, he was inflicted with paralysis and his last works were done in part by his many pupils. He died at the age of sixty-four in 1861, one year after Yokohama opened its port to foreign vessels.

Research by: Howard A. Link.

Person TypeIndividual